User Reviews

Rating: really liked it

I've never read a book so thoroughly detailed. At times it felt like a day-by-day account of his 37 years. The book establishes early on that Van Gogh was at best "quirky" and at worst had a few disorders, but hey, who doesn't. I'm not a psychologist, but when you are sleeping with your walking stick in your bed to punish yourself, I don't know, that's probably a red flag for later developments. For the first 600 or 700 pages, I developed a dislike for Van Gogh; he's an unlikeable loser. But by the end there is empathy and compassion for all that he went through. Of course, he could have just gotten a job at some point, but then the world would be the lesser for not having his art. He taught himself, researched, studied, applied new techniques, which all lead to him 'becoming' Van Gogh. The book doesn't really spell out exactly why Van Gogh and his art became a worldwide phenomenom. It doesn't critique the art; the book just details the life. Most people are familiar with the art from Van Gogh's final two years, the fact that he cut off his ear and killed himself. Obviously, those few items don't tell the whole story, and the whole story which at times is repetitious is ultimately fascinating. He lived in interesting times in Europe and in art. Everyone wrote letters, kept family histories. Van Gogh exists at this crossroads between the old ways of society of manual labor and a new era. He was a craftman who appreciated the working man. He was relentless. You have to appreciate that.

At the end, I was sad that he passed; he had found his stroke, his style of painting that combined many of the interests and influences that became beloved by the world. But I was also relieved for him. He did not have an easy life. When he died, he became the embodiment of the suffering artist. The world learned of this solitary figure and fell in love with what they took to be a romantic figure.

The book theorizes that he did not kill himself and they make a very understandable and believable case that he did not.

The authors read everything that Van Gogh wrote and everything that Van Gogh read. The level of researching is amazing. The writing pulls you through a lengthy and detailed story, a life worth examining.

Rating: really liked it

I have a plethora of intense feelings after reading this extremely arduous book. I've learned so much and have this gnawing sadness in my heart for the misunderstood, broken, fragmented, tortured, loving, frustrating, creatively gifted, and masterfully talented soul.

Where do I begin? Upon being introduced to Van Gogh’s (pronounced GUH) family it seemed Vincent was always desperate for his mother's affection. He longed for moments of solitude and tenderness from a woman that he revered more than anything in the world. Vincent, one of 5 siblings always seemed, to his parents, to be peculiar and difficult to handle. His melancholy mood made them uncomfortable more than curious.

In his early years, Vincent struggled to finish his schooling and hold a job. His mental health played a role at various moments in his life. It truly is an atrocity to think that Vincent is known today, most notably for the cutting of his ear and his so-called "suicide," but he was much more than that.

He had a deep, meaningful, and oftentimes catastrophic thought process in which he would dwell and ruminate over things that overtook his thinking. He seemed to suffer from what today would be diagnosed as anxiety, bipolar disorder, and possibly elements of a borderline personality (the author never explicitly mentions these diagnoses, but from the reading, this was my assumption).

His brother Theo, the one constant in his life, was the brunt of many of Vincent's desperate attempts to find a sense of peace and stability in his life. Vincent would often write letters to Theo, which is where the author Steven Naifeh did his research. In those letters, Vincent was often extremely demanding of Theo's attention, time, and money.

Vincent's friendship and deep admiration for Paul Gauguin is also discussed in the book. Vincent had a chaotic and fraught relationship with Gauguin. He would be desperate for positive admiration from the painter. Mostly, Gauguin would criticize, but once Vincent's show was seen in Paris there was admiration for many of his works.

His relationship with Gauguin and many others was often conditional, and when things didn't go as Vincent wanted he would lash out with extremely negative opinions and thoughts. This became a struggle for Vincent as well as the people who loved him.

Van Gogh: The Life is such a thorough and intensely satisfying production of ideas in which the author did a retelling of every moment of the painter's life. I will say, sometimes things felt repetitive, and the point could have been made clear with less detail.

Yet, it was interesting from his time as a devoted Christian zealot to his obsession with brothels and prostitutes. Vincent was never able to find any sense of zen. He often said he worked best under the most distressing moments, which shows. Some of his best works were done during his time at the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Remy, southern France.

The author Steven Naifeh gives the reader an absolute mind-bending, thought-provoking analysis of how Van Gogh may have died. I, for one, am now a believer. Regardless of how broken and tortured the painter was, the way his last few hours played out in no way add up to a suicide. Naifeh discusses this in the prologue of the book. The entire read is well worth it to get to this important and curiously accurate analysis.

The forever truth of how someone is defined is only appreciated after death, which seems to be fitting for Vincent Van Gogh. It was shortly after his passing that people began to be fascinated by his daring works of vibrant colors and strong brush strokes.

If I could talk to one person from the past, I would love to tell Vincent Van Gogh that he made it. It was quite heart-shattering to think of how many of his inner demons and struggles prevented him from being vindicated for his art.

In a few months, I have the pleasure of going to see Van Gogh's immersion exhibit, and this read came at the perfect time; a sheer work of genius that gave me wonderful insight into a truly brilliant painter’s life.

Thought-provoking and well researched. In my opinion, Van Gogh: The Life deserves nothing less than 5 shining stars!

Rating: really liked it

By far the saddest biography I have ever read, VAN GOGH is also one of the most stirring and superbly detailed biographies I have ever read. That Vincent van Gogh's life was such a brutally painful and difficult one should not deter readers from embarking on this massive journey, yet the fact that a 951-page book reaches page 750 before the subject has what could genuinely be called a period of happiness is a testament to the skill with which the book is written, for despite the utterly depressing nature of Van Gogh's life, the authors make it a terrifically compelling one to read about. The amount of detail, in no small part but not entirely due to the prodigious correspondence that exists between Vincent and his brother Theo, is as complete as any biography could (or should) aspire to, and by the end of the book, one feels as though as though one has lived alongside Vincent through almost his entire life. The book approaches yet manages to skirt oppressiveness of detail, a superb feat given the consistency of the arc of Van Gogh's tortured life, and while the repetitious nature of Van Gogh's behavior and follies becomes almost as tiresome as it must have for his family, there is nothing in the book that should have been left out. The authors, too, have a splendid sense of art and how Van Gogh's mind was reflected in his art, and all this is described with clarity and, and at the same time, poetry. I wept as I reached the end of Vincent's life, in part because it was such a sad and unhappy life, but also because by the book's end, I felt as though I knew and understood the man behind some of the greatest art in history. Such should be the goal of every biography.

Rating: really liked it

I don't usually write such lengthy, or such scathing reviews but this time I feel compelled to. First of all I will say that once I picked up this book, I really couldn't put it down. It was an incredibly intriguing, detailed, and fascinating story of a man we all know and some of us love despite his "issues". The authors spent ten years researching and writing this tome and in the end, I think they used their Harvard Law credentials to convict the subject of the crime of mental illness and of being a person no one else could tolerate. Clearly they'd done their research, but the way they chose to portray Vincent from the very beginning of his life, and of this book, was inexcusable. Like slimebag lawyers using other people's perceptions and recollections to make their case, they manipulated the “evidence” to support their claims.

Having read Volume One of Vincent van Gogh The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, edited by Leo Jansen, I picked up this book thinking it would fill in some of the gaps that might help me have a better understanding of the subject: van Gogh and his life. (You can read all of his letters too, online for free, at http://vangoghletters.org/vg/.) Once I had caught up with Vincent's life in this book at the time his letters began, I noted how the authors would take his words, use them out of context to prove their point, ascribe questionable meaning to what he said and apply negative, inflammatory descriptors whenever possible to what he said and how he said it. Imagine my surprise when Letter 155, which I thought was a most lengthy, beautiful supplication, was described by the authors as “pages and pages of defensive posturing and convoluted casuistry...using veiled constructions.” The authors admit in the addendum at the end of the book to reading between the lines and assuming that what Vincent said was not always what he meant, that he was manipulating people because he took a different tone depending on to whom he was writing. But don't we all do this? And how do they justify this interpretation of his sentiment?

In any case, the list of contentious words used over and over to describe Vincent and his behaviour is, I find, reprehensible: maniacal, paranoid, delusional, volatile, leaps of fantasy, rapture of enthusiasm, leap of unreality, fits of frustration, repeated failures, storm of protest, lashed out, lamented, moaned, complained endlessly, spasm of regret, fever of dread, erupted, boasted, sputtered, admonished, pleaded, begged, rhapsodised, wailed... How they can apply this interpretation to Vincent's written words, which to me could be taken in a completely different way, is unfathomable. These descriptors were used from the beginning as evidence that he was mentally ill from the start. I dare you to read the letters and form the same conclusion. The rest of the information about Vincent is nothing but heresay. Imagine having a strained relationship with your parents and someone writing about you basing their interpretations of your behaviour on how these other people felt about it. What these other people saw. And the gossip they spread. I assume the authors had other sources of information but they cleverly used ubiquitous “quotes” and referred the reader to some website which supposedly contains every detail of who said what and where they got these “citations” which makes it virtually impossible to fact check their assertions. The assumption that because it's quoted and cited, that it's actually a correct interpretation of the situation would be absurd.

My disgruntlement is not about the alternative ending, which I actually find more plausible than the story of Vincent's attempted suicide. I do not question the details of his life: where he went, who he met, what he did. What I object to is the way they portray the man. They paint such an unflattering picture of a man who, if you read what he actually wrote, comes across as an extremely intelligent, sensitive, passionate, exuberant, persistent, energetic, chatty, needy, kind, spiritual, learned, and lonely man who loved his parents, wanted to please and help them and others, and who wanted a deep connection to other people and to the world around him but was thwarted, chastised, bossed around, controlled by others, bullied and ostracised wherever he went. To be sure, it takes two to tango, but I object to the way the authors place all the blame on Vincent himself when in so many cases he appeared to be reacting to the way other people were treating him. His sad story is a tale of traumatic events, wrong turns, bad decisions, and a striving for something that he could only achieve posthumously. At the very least Vincent was a deeply philosophical man who understood something special about the nature of people and the world. It's too bad he wasn't able to express it during his lifetime in a way that other people could perceive it. If you want to find out about the superficial details of Vincent's life you can read this book and appropriate the opinions of other people. If you want to understand Vincent better, read his letters and look at his paintings. You'll get a much clearer picture of who he was by what he, himself, left behind.

Rating: really liked it

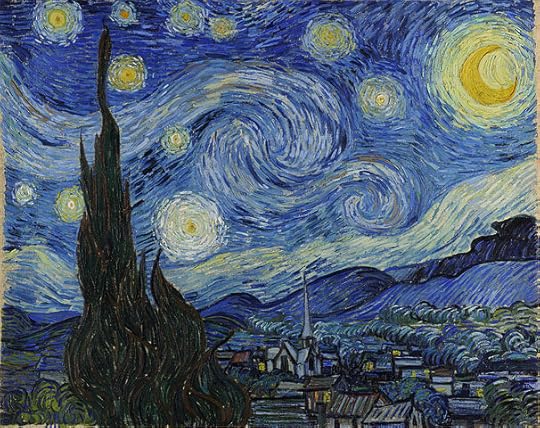

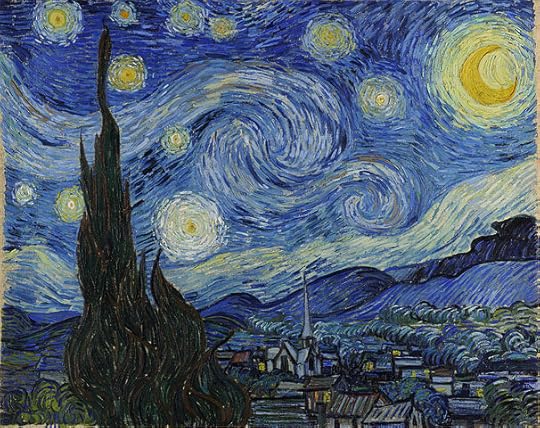

A social pariah's life: stalking shades and hues, skirting the cliffs of sanity, into the forever's starry night.

Fascinates and inspires.

Rating: really liked it

He expressed his truth in letters, and on canvas, immortalized a complex and beautiful soul.* Pulitzer-winning biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith have gleaned a thorough and insightful portrait of Vincent van Gogh, primarily from meticulous research of his extensive letters to his brother Theo, who was a successful art dealer in Paris and his most ardent confidante and supporter. Vincent's epistolary story reveals thoughts and feelings ranging from spiritual, philosophical and poetic to muddled, indecisive or obsessive, his fevered search for

truth in a vision that would inform his artistic development and his greatest achievements.

From childhood, Vincent would display disruptive behavior unpalatable to his minister father and strict mother, who possessed somewhat of a cool, obsessive nature herself. He enjoyed sketching since a young lad and having uncles in the art trade would have given Vincent a good start in his young adulthood, but his erratic manner often alienated people and that employment abruptly ended.

His failed attempt as a missionary, loss of faith, and what he must have seen as rejection from his parents, reawakened in him the sense of abandonment and loneliness that had taken root as early as his schoolboy years when he felt an outcast. Naifeh's and White Smith's extractions from his letters during the production of his early paintings show an internal pathos that reveal what we know today of his developing mental illness, which when spliced with artwork featuring peasant life and nature, a need to express his truth and a progressing avant-garde aesthetic (at the time called nonsense from a madman) define the tortured, harrowed life between swings of violence and utter degradation; and, on the other extreme, illuminate the evolution of his brilliance.

“That mind has for so long been preoccupied with things our society today has made impossible to solve and which he, with his kind heart and tremendous energy, nevertheless fought against.… He holds such sweeping ideas on questions of what is humane and how we should regard the world, that one first has to relinquish all one’s conventional ideas in order to grasp what he means.” - Theo van Gogh

Some of his most revealing paintings are his self portraits as he peers into himself quizzically, searching perhaps for the sentiment he yearns to express in his uniqueness.

"I want to get to the point where people say of my work: that man feels deeply, that man feels keenly....I want to paint what I feel and feel what I paint.”

"I want to get to the point where people say of my work: that man feels deeply, that man feels keenly....I want to paint what I feel and feel what I paint.”Vincent's passion for landscapes and pictorials of earthliness populate his extraordinary legacy and often reflect his psychological state. In 'Wheatfields with Crows' is depicted the fierce changeability of the multifaceted natural world that filled his vision: the rolling, inconstant rhythms of wheat against the menacing turmoil in the sky - a representation of van Gogh, the artist on the brink of an emotional storm.

Ironically, some of his most acclaimed work, specifically one most popular masterpiece ( and my personal favorite), of undeniable perfection in nature's glorious splendor: 'Starry Night' was painted in the asylum at St. Remy - the explosive bursts of light and roiling quality of the sky are indications of a psychological maelstrom which his doctors claimed were epileptic.

"How your brain must have labored, and how you must have risked everything to the very limit where vertigo is inevitable,"

"How your brain must have labored, and how you must have risked everything to the very limit where vertigo is inevitable," said Theo when he saw the swirling, intemperate painting.

I was a little taken aback with the biographers' belief that his tragic end was no suicide, contrary to the accepted norm that the fatal wound was self inflicted, surmising instead that a teenaged ruffian named Rene Secretan, known to brandish a gun and who often bullied Vincent: might have shot him, but that Vincent covered up for the boy in his desire to spare him.

Vincent left behind a life so well expressed in his letters that the authors could create this passionate portrait of an artist as a troubled man, which at 1000+ pages is itself a masterful work of art, a painfully heartrending reflection of an intelligent, colorful yet restless life, who suffered in his quest to articulate meaning in his art, and died not realizing that he had already done just that.

"It must be good to die in the knowledge that one has done some truthful work."* me

Rating: really liked it

During this summer I had the chance to visit Van Goghs museum in Amsterdam and after my return home I just had to find out more. Before my trip I looked up interesting locations to visit up on TripAdvisor and of course this museum was in top 5. Seeing this my thoughts were:

1) Oh yeah, he was Dutch, wasn't he... and

2) I really don't know more about him other then the ear incident, Sunflowers and Starry Night

This gap in knowledge had to be fixed!

Vincent was an incredibly tragic and passionate figure, battered by his own manias his entire life and always dreaming of fame and redemption he never got. It was hard reading about all of his personal, interpersonal or financial failures. The blow by blow accounts of all of his friendship meltdowns struck me quite deep and made me feel quite sorry for him, long before the ear incident. Which undoubtedly helped in making himself into a legend that he is today, and one of the best representatives of struggling artists everywhere.

This book is overwhelmingly thorough, it feels as if the only way to find out more would be to read all of his letters myself. Thankfully for every painting mentioned I could recall it from the museum or use the internet to look them up (this was especially useful for the mentioned paintings that were made by his contemporaries). I personally loved this book, but I see a lot of other reviewers say that the author portrayed Vincent in overly negative light in this book, looking at everything through the lens of mental illness. To some extent I can see why people might have a problem with this, but I would have to read more biographies and probably the "My Dear Theo" collection of his letters to see if they are right...

I might start looking into this in a few years (it was a 900 page book, I need a break from this topic).

Rating: really liked it

I am finally finished and spent a lot time skimming through chapters to avoid repeats, overblown accounts of everything, and dull negativity.

I got sick of re-reading pages on the dysfunctional or negative relationships Vincent seemed to have with every man, woman, and child he ever met. How many blow by blow accounts does a person need to read?

Sure, V was moody, argumentative, opinionated, and obsessive, but the man MUST have had good qualities. To the authors V is a burden and haunted, they barely dip into their own box of word-colour to paint the man's character with some yellow, blue or red.

However, they do use hyperbole to describe letters and encounters in a way that is based purely on their opinion. Signac writes "tepidly" to invite Vincent to Cassis - how do the authors get this word when the letter quoted says, "come do a study or two in this pretty country."? What is tepid about that? Why do they always skew Vincent's encounters so they are anti?

They write about how negatively Theo responded to Vincent, yet, after V died, Theo obviously broke with grief. Theo describes Vincent to his Mother, "he was so my own, own, brother." And this isn't a retrospective romantic notion - and "romantic" is how the author's describe any positive comments made by the brothers, it is a heartfelt expression of a, for the most, loving relationship.

The authors harp on and on about how Vincent spent his whole life trying to tell others how to think, but this book does the same thing.

And I can only think Why?

Why is this bio so dark? Why don't they offer a lucid explanation or two? Why don't they explore the mental illnesses in the family more?

Especially in light of the fact 3 of them ended up in asylums at some point or other?

And I do not agree that this bio is well written. The author's are competent writers but if they use far too many adjectives to create a biased account of a life then it becomes a sort of polemic that can't be trusted.

Vincent led an often troubled, sometimes glorious, often ordinary (albeit extraordinarily artistic) life amidst what appears to be mental illness (bipolar?). His life must be contextualised by this instead of being treated as if he could choose a different way of being. Because this bio doesn't do that it is not to be taken seriously. Far better to read about Vincent without all the sensationalist language and overdone description than waste time on this bloody great doorstop.

Rating: really liked it

A very comprehensive biography of an intense and passionate man that provides a deep insight into his mind and creative process. A thoroughly researched portrait of Vincent's tragic life. Vincent initially comes off as an arrogant and self-destructive man. But he was as much a victim of the society that rejected him for being different. Vincent would start his career as an art dealer. But he was neither smooth talking nor good with people, which would mean an end to his career as an art dealer. Faced with his failure and rejection from his family, he would try to find solace in religion. But his later foray into a career as a missionary would also end in a similar failure. The intensity and passion that he brought to his attempted career as a missionary or a preacher, and his constant search for meaning would alienate most of his peers.

Faced with his failure in all his career endeavors, and having been rejected and shunned by family and friends and women, his life would soon spiral downward into intense melancholy and guilt that would mark his painting career. Throughout his artistic career, he would search for solace and meaning, often keeping emotional crisis and complete breakdown at bay by his furious dedication to his work and delusions of future success. It is remarkable the amount of intensity with which he worked despite being rejected and ridiculed at every step. His art was his solace and his mode of expression. He puoured his emotional and spiritual feelings into his work. He may not have been a good draftsman but his passion and intensity speaks through his colours.

The authors here also make a good case that the gunshot wound that killed Vincent might infact have been an accident, a result of an altercation rather than suicide.

A remarkable and heartbreaking biography.

Rating: really liked it

This was by far the most incredibly detailed biography I have ever read but also one of the most fascinating books in general I’ve ever picked up. I have always been drawn to van Gogh’s art and also him as a person, but admittedly didn’t know much despite having gone to the museum dedicated to him twice. He is such a legendary figure but the real story, meticulously researched and written here, is absolutely tragic. I find myself wanting to reach out to anyone I’ve ever been mean to in my life to apologize and afford them the courtesy that was denied to Vincent. He was a social outcast, had zero employability, and depended on his brother Theo in every aspect of life (especially financially). He tried so, so hard—that’s my main takeaway. Vincent tried. He tried to please his family, he tried to get a job to support himself, he tried to make beautiful art, he tried to find a wife, he always tried. The authors’ note on his death is incredibly interesting; they suggest that it was the result of an accidental shooting by a local teenager who regularly tormented Vincent. While Vincent was certainly depressed, the authors argue that he never truly was suicidal and his death occurred because he merely welcomed it as it happened and told authorities he shot himself in order to protect the boy. If this is the truth (I believe it, but we’ll never truly know) I’m even more impressed and devastated by Vincent. I’m reminded of the Doctor Who episode in which a museum curator calls him the best painter of all time, a man who took his debilitating pain and created ecstatic beauty—I absolutely agree.

Rating: really liked it

Biographies can be a dry subject, especially if they have over 900 pages - and for that reason, I must compliment Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith for having written such a compelling and addictive book. In this absolute page-turner, they have not only developed a top-notch academic research work, they have also managed to write it with such skill that it turned into a gripping, inspiring novel-like tale. Using the painter's letters, they succeeded in making his personality and struggles come to life, and have drawn a complete psychological profile of Vincent, the man, while highlighting what makes the work of Van Gogh, the painter, so mesmerizing.

In this book we discover that Vincent was by no means a perfect man - selfish, manipulative, stubborn and prone to anger - but by the end of the book you can't help but feel a great sadness for this unique, troubled man, stuck in a lifelong fight with himself. I dare say that even if you are not that interested in art, you'd be captivated by Vincent's inspiring, although tragic, life story. Despite it being 950 pages long, I wish it could have been even longer - I will miss this book.

Rating: really liked it

This biography was certainly a massive undertaking by award-winning authors. It's well-researched and well-written all right. But the underlying view of Vincent as a man with basically a horrible personality who created his own problems seems short-sighted and unfair. Are the authors re-doing the Jackson Pollack book? This book made me go back to read Vincent's incomparable letters to Theo. There are other books that are superior in contemplating Vincent's mental and physical health issues/disabilities from a distance. These authors don't care; to them he was a spoiled (!) brat who took advantage of his friends and family.

Rating: really liked it

“Trust in God who sees everything and knows everything,” said Vincent Van Gogh’s mother, Anna, “though His solution may be deeply sad.” This is a fitting summary of one of the saddest family chronicles imaginable. Nearly everyone in Vincent’s family ended life at least disappointed, if not depressed or insane. The glorious French sunlight that Vincent left us in his paintings covers a shadowy lifetime of seemingly unanswered prayers for harmony and wholeness in his family. The massive biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith portrays Vincent’s life as a long plea for reconciliation—with his pastor father especially, but also with his stoic mother, his enabling brother, and with fellow artists and the Paris art scene that didn’t understand him or accept him. It’s hard to see exactly where and why this breakdown of the family occurred—the biographers endeavor to present the bare facts, without interpretation of what was “really” happening (though of course any biography is an interpretation, not just the facts). The authors put a negative spin on some aspects of Vincent’s growing-up years that seems to me based more on knowing the tragic outcome than on a neutral view on what was really said and done.

What we learn for certain from this accounting of Vincent’s life is that he was an extraordinarily difficult person to get along with. He struggled all of his adult life with deep feelings of inadequacy, failure, and regret. With hindsight, we see many places in his story where, with our better understanding of depression, interventions could have greatly helped him. But at the time, even near the end of Vincent’s life when he was admitted to asylums, no one knew what depression was. The best diagnosis doctors could offer was that Vincent suffered from a “latent epilepsy” that caused mental seizures, not physical, which led to his darkest periods of depression and rage. The only treatment doctors could prescribe was to keep him in a safe place where he wouldn’t be able to harm himself or others. And after a certain period of apparently good mental health, they saw no reason not to release him back to the world, where he would meet exactly the same situations that brought about the madness in the first place. It all seems sad and ludicrous now, which shows how much we’ve learned in the decades since (and suggests how much we still have to learn).

In those later years of Vincent’s life, when he was in and out of asylums, the biographers want to suggest that his family, and even his beloved brother Theo, were heartless and cold toward him, not reaching out in love and support. But after the hundreds of pages detailing how awful Vincent was to his family, again and again, the reader wants to throw his hands up and say, “Well, what were they supposed to do, though?” They had given Vincent chance after chance and seen him throw it back in their faces every time. I know that by that point in the biography,

I was exasperated with him! And only in his late 30s, there was probably little thought that the end was so near. I can understand if the family assumed that this was a short period in his life where he was safely looked after by someone else in an asylum.

“Exasperation” is a key word for my feelings at a lot of points in this 900-page biography. I wanted to learn more about Vincent, beyond the legend, and I suppose this book met that need. But it is a

long book. I don’t fear long books—

Middlemarch is my favorite novel and

Les Misérables,

Crime and Punishment,

Anna Karenina, and other lengthy tomes are also favorites—but this book

felt long. The writing is clear and precise, but something about the style felt ponderous and dull to me. All of it is “fine,” but none of it is “beautiful.”

The barrage of minutiae about Vincent’s day-to-day life really wore me down (one reason that I spent months reading this! There always seemed to be another book that I’d rather be reading, until I settled down and forced myself to just finish this one). Before reading the book, I thought that I liked him and his work. Having finished this biography, I find that he has now been thoroughly demystified for me. Getting to the end and finding that even his enduring legacy was in many ways manufactured by people who wanted or needed him to be famous—not that contemporaries saw his works and were instantly blown away by them (though I’m sure that’s some part of it, too)—was particularly disheartening. I would still like to read a collection of Vincent’s letters, because I sense that perhaps the biographers have given a negative reading to some of his writing; but I wish I felt more affection for him after learning this much about his life. It is at least nice to be able to place his work within a timeline and a story—it’s interesting to know, for example, that the sheaves of wheat painting I see at the Dallas Museum of Art is from the end of his life, when he was living in Auvers and still dreaming of recruiting Theo and his family to join him there. But for most people who want to learn about Vincent, I’d recommend a shorter book—probably one that focuses on his life and work from the period at Arles onward. That phase includes most of his best-known works, and what comes before is extremely repetitive and bleak. A shorter summary of his life up to that point will be sufficient for most readers.

I look forward to watching

Loving Vincent and re-watching

At Eternity’s Gate, which I think I’ll appreciate more this time.

Rating: really liked it

It's no wonder to me now that these truly gifted biographers won the Pulitzer Prize for their life of Jackson Pollock, assuming, of course, that their prose is as "intense" as the writing in their most recent collaboration.

After 300 pages, I haven't detected a sentence or a paragraph that fails to extend their narrative of Van Gogh's life (all 900 pages of it, less the 5000 pages of documentation that resides on-line) or enrich their characterization of this terribly difficult man, whose shifting realities, imperturable sense of entitlement and nearly intolerable temperament, alienated nearly everyone he ever engaged - even the most sympathetic.

I find their subject entirely fascinating, their treatment masterful, and their writing a model of splendid exposition.

11/22/11. After 600 pages, I find that their prose is as engaging - and as truly awe-inspiritng - as ever. I must also say that I find their meticulous and thorough descriptions of every repetition of Van Gogh's cycles of highly disturbed behavior, which destroyed every relationship he ever formed, a bit tiring. I understand that the authors aimed to document every moment of their subject's life, every hostile encounter of which there is even the least little scrap of evidence, and I applaud their epic industry. But I am beginning to skim the pages that present another instance of more of the same. Their book is as good a biography as can be written I suppose, and in some ways it rivals Kershaw's "Hitler." Each author's mastery of their craft doesn't impose an obligation on me that I savor every word, however, especially after I've tasted a particular dish twenty or thirty times over the last three days.

11/30/2011. I just finished this biography, and I can only give it a five-star rating. It is truly one of the most successful examples of the biographer's craft that I have encountered in my fifty years' devotion to that genre. I suspect that the authors will win another Pulitzer, perhaps a National Book Award, among many others, for their achievement. Nonetheless,in cases of products of such superlative craftsmanship as "Van Gogh: A Life" I often wonder if, for the sake of yet another perfect sentence or a brilliantly constructed paragraph, authors of non-fiction ignore or modify certain inconvenient facts. I still wonder about this particular life of Van Gogh, despite the excerpts of letters and memoirs that the authors aduce in every segment of their book, and despite the 5000 pages of further documentation that they provide on their website, www.vangoghbiography.com. I suppose I could allay my nagging concerns by tracking down the relevant footnotes, examining sources and evaluating corresponding sections of their biography. But I certainly don't intend to spend time in that way. And besides the world is full of art historians and subject matter experts (SME), who, no doubt, are probing, even as I write, every statement and conclusion that the authors committed to paper. If there's an unsupported claim in any of the book's 875 pages, these SMEs will certainly draw the world's attention to it. Highly recommended.

Rating: really liked it

I seldom write Goodreads reviews and am not about to start to, but this book has deeply moved me - at times to tears. It would seem unjust to simply

mark it as read and move onto the next read.

Many know Vincent van Gogh for cutting of his own ear and his crowning achievement: The Starry Night. A few know the details in between; the frustrations and let-downs that had led to Vincent almost amputating his left ear, after which he sought respite at the Saint-Paul asylum, from which he painted his second starry night, welding both real-life observation and imagination - and that he had considered it a failure. These are but a few details that do not even begin to cover the rich and heartbreaking life of Vincent van Gogh; one that overflowed with torment, beauty, sentiment and color.

For fans of Vincent, such as myself, this is a must-read. In eloquent, almost poetic language, and thorough attention to the smallest of details, this book provides an intimate, day-by-day account of Vincent van Gogh's life; which has been anything but easy. I am grateful that, in spite of his despair, Vincent continued to paint and write his true-hearted brother Theo - for it is from their correspondences that we had gleaned insight into the extraordinary life of an extraordinary man; one the world, at the time, was committed to misunderstanding.

Upon hearing of Charles-François Daubigny's death in 1878, Vincent wrote: "it must be good to die in the knowledge that one has done some truthful work and to know that, as a result, one will live on in the memory of at least a few." I wish there were a way for Vincent to know that his truthful work would be celebrated into perpetuity and that his beautiful, gentle soul would live on and continue to touch and inspire lives, even today.