Must be read

- A Means to an End

- Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know About the People We Don’t Know

- A Far Wilder Magic

- Brave Girl

- Family for Beginners

- Second Chance Magic (Order of Magic #1)

- We Were the Mulvaneys

- Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs? And other Questions about Dead Bodies

- Sense & Second-Degree Murder (Jane Austen Murder Mystery #2)

- Kindle Paperwhite User’s Guide

User Reviews

Petra X 95% hiatus, no time for play just work

In an interweaving between the elements and stories, Primo Levi tells his life. But he chooses episodes to relate carefully and never discusses his children. At the end he tells us, that his writing was only ""partial and symbolic". The man who wrote so much and so tellingly of Auschwitz in If This Is a Man remains a mystery.

The greatest mystery of all, to me, was his death. At 67 he fell over the balustrade of the stairs down from the 3rd floor of the house he'd lived in all his life (except when he was imprisoned in Auschwitz). How do you fall over a stair rail? Was it suicide? Was he the last victim of the concentration camps?

Rachel

You know how you read a sentence and copy it down because it's so good? In this book, I'd find a sentence, and go to copy it and realize it relied on the one before it, which relied on the one before that for its complete meaning. So I'd copy down whole paragraphs, whole pages, because Primo writes in integrated, seamless blocks of meaning. Which is enviable.

Other than that, I want to give Primo a big kiss, buy him a beer, and ride bikes with him in Italy.

Ben Sharafski

In a series of interconnected stories (a loose structure that inspired my own book), straddling the border between memoir and autobiographical fiction, Levi tells the story of his life: his centuries-old family origins, his years as a socially awkward young man, the nightmare of Auschwitz and the years of obscurity as an industrial chemist who also happens to write a bit on the side - books that no one wants to read. Told with candour, precision and humility, this is a true tour-de-force.

Jim Fonseca

Each chapter is named for an element; some chapters are autobiographical, some are essays, some are vignettes of people he knew and their careers in chemistry; two are short stories about metal prospecting and mining with hints of fantasy. Most are autobiographical and through these we learn a bit of his childhood; his boyish fascination with chemistry experiments which grew into his college education and career as a chemist; his puppy loves and courtship and his imprisonment in a labor camp during WW II.

There’s a lot about language derivation, especially of names. For example, the mixed Jewish/Piedmontese dialect in the fabric shops of that Italian region gave Italy a lot of its fabric terms. And he worries that while he can speak it (Piedmontese, essentially a spoken language), it loses its authenticity from his book learning rather than native fluency. It’s fascinating to learn things such as urstoff in German means element or primal substance.

Here’s a quote chemists will love: “…the nobility of Man, acquired in a hundred centuries of trial and error, lay in making himself the conqueror of matter.”

We even have a passage about fake news: “…how could he ignore the fact that the chemistry and physics on which we fed…were the antidote to Fascism…because they were clear and distinct and verifiable at every step, and not a tissue of lies and emptiness, like the radio and newspapers?”

Apparently fake news is a theme of the great Italian writers of this era because it reminds me of a related passage I quoted recently from Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler: “We’re in a country where everything that can be falsified has been falsified: paintings in museums, gold ingots, bus tickets. The counterrevolution and the revolution fight with salvos of falsification: the result is that no one can be sure what is true and what is false, the political police simulate revolutionary actions and the revolutionaries disguise themselves as policemen.”

Occasionally there is a theme of chemical mixing and the mixing of Jewish and Christian culture. The author was forced to work as a chemist in the Auschwitz labor camp. He later corresponded with his German supervisor at the camp. Several passages deal with the tense relationship between the Italian fascists and the Jews such as:

“…one could be polite, one could even help him [a Jew], and even boast (cautiously) about having helped him, but it was not advisable to have human relations with him, nor to compromise oneself too deeply, so as not to be forced later to offer understanding or compassion.”

Levi could not receive his college degree since awarding a degree to Jews was prohibited; nor could he initially get a job since the “racial laws forbade it.”

The author makes some humorous but nasty comments about librarians. With apologies to the many users on GR who are librarians, here’s one passage:

“The librarian…presided over the library like a watchdog, one of those poor dogs that are deliberately made vicious by being chained up and given little to eat; or better, like the old, toothless cobra, pale because of centuries of darkness…she was small, without breasts or hips, waxen, wilted, and monstrously myopic…She gave the impression of never having been young, although she was certainly not more than thirty, and having been born there, in the shadows, in that vague odor of mildew and stale air…she stank of mothballs and looked constipated."

I read somewhere this was the greatest science book ever written. No, I prefer Richard Feynman, but it’s pretty good. Translated from the Italian.

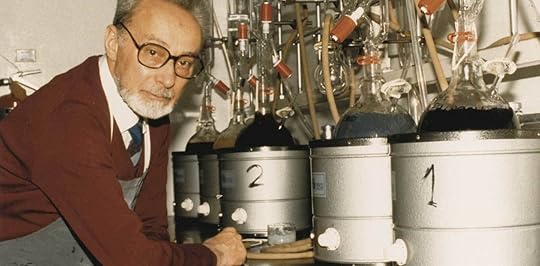

photo of Primo Levi from itascabile.com

Paul Bryant

Every suicide is like a nail bomb full of vicious questions and the questions don’t care where they land. Why didn’t somebody do something? – there’s one. Surely there must have been signs. Right there is a triple blow delivered to the bereaved partner and immediate family. They’re reeling from the event, then they have to conclude this depression, this malaise, was so acute it blotted out even thoughts of themselves in the suicide’s final minutes. And after that comes the unspoken accusations and avoidings by friends and associates. (Why didn’t they see and having seen taken steps?). Some suicides still hang like paradoxically visible black holes of misery up in our skies, Sylvia Plath, van Gogh, David Foster Wallace, Kurt Cobain, Ernest Hemingway, BS Johnson, Mark Rothko.

Primo Levi committed suicide at the age of 67 in 1987. The repercussions were uniquely distressing. He had been the embodiment of an idea that is so cherished it’s nearly unbearable to think it may not be true. The idea that a person can go through the worst and most inhuman experiences, in his case Auschwitz, and survive not only in body but in spirit too, and not become corrupted, and not destroyed. Levi’s books were and are the clearest-eyed, most lucid, most carefully discerning, and most humane books about the Holocaust I have come across. The idea that Auschwitz finally got him, 42 years later, that Hitler had extracted one more posthumous victory, was horrible.

And this final act now throws a long shadow over all his great writings, so that we loop round on ourselves and almost catch us yelling and denouncing Levi for doing such a thing, and then feel instant shame at such a thought. This suicide involves Levi’s readers inevitably in these psychological traps.

Of course you can argue that the depression and anguish which led to the suicide might have a whole other aetiology of which we are completely ignorant. It’s possible, and it’s a comforting thought, were it not for the continuous theme in his various writings being Auschwitz and the Holocaust from If This is a man (1947) to The Drowned and the Saved (1986). Or - you can argue that it wasn’t a suicide at all, it was an accident – an old man fell over a balcony. There was no note. The concierge of the block of flats had spoken to him minutes before he died. He seemed okay. But both his biographers think it was suicide.

We have to say that it doesn’t matter. The work is the thing. Rothko’s canvasses are not affected one way or another by his death just as Wuthering Heights would be just as great a novel if Emily Bronte had celebrated her 100th birthday on 30 July, 1918, as World War One was coming to an end. It doesn’t matter.

The Periodic Table is a quirky memoir of a Jewish-Italian chemist. There are elements of cool humour throughout and hardly a trace of bitterness.

Kinga

Chemistry as a metaphor for life. Blurb writers love phrases like that. They are short, succinct and intriguing. But how hard is it to write something that would deliver on such a promise?

I had never read anything quite like ‘The Periodic Table’. It more than delivered – it exceeded my expectations. The book is a beautiful marriage of life and science, perfectly accessible to a regular reader. The truth is that anything can be fascinating provided it’s explained by a person truly passionate about the subject (and it doesn’t hurt if they are also mind-blowingly good writers like Primo Levi).

You might know Primo Levi as an Auschwitz survivor and you might worry that ‘The Periodic Table’ would be too dark of a read. But it is not ‘If This is A Man’. Holocaust is still lurking around shadowy corners of this book and it is quite obvious that Primo Levi would be a different kind of writer if it weren’t for that trauma (some might even ask if he would be a writer at all) but this collection of anecdotes, recollections, allegory and glimpses is, I would venture to say, an ultimately almost positive (if not downright optimistic) work.

The very first story might be a little odd and discouraging but either soldier on or skip it altogether – it’s not really representative of the rest of the book. I found reading about the intricacies of a Piedmont dialect with its borrowings from Hebrew rather fascinating. I am interested in the process in which words change their meaning entirely (not unlike they did in cockney rhyming slang) but I can appreciate that such linguistic elaborations are not to everyone’s taste.

Further chapters – each named after a different chemical element document Levi’s life as a chemist and they are often funny, tender and bitter-sweet. They are intersected with fictional short stories which read like fairy tales and where chemical elements take on almost mythical qualities.

The most striking story is the penultimate one in which Levi comes across a German who oversaw his work in the laboratory in Auschwitz. Like a true scientist Levi wants to rationalise and understand his feelings. He wants to know what it is he expects from the encounter. His struggle to organise the swarm of emotions is probably the most touching part of the book.

‘The Periodic Table’ is not a science book, whoever calls it that has no idea what they are talking about. It’s a book about the love for science. It’s about what every scientist wants us to believe – that their subject is not some obscure knowledge of interest to few, but it’s life and reality that makes us breathe, move and think. The last story in the collection spells it out for you in case you missed the more subtle hints in the previous chapters. I liked it a lot because it reminded of the times when, as a little girl, I fantasised about the history of atoms in my body – where they had been before me. I imagined them as a part of dinosaurs, king and queens, old houses, wild horses… The story is Levi’s crown argument for his thesis that it is only through matter (not sprit) we can know the universe. (And this is a thesis I can easily believe in – it appeals to me. I am not what you call ‘spritual’).

If you made it this far in my review, I will reward you with a link to an excellent interview with Primo Levi in the Paris Review of Books: http://www.theparisreview.org/intervi...

Orhan Pelinkovic

Levi names each chapter by a different chemical element and compares and draws parallels between the elements, or their characteristics, with the features and traits of his experiences. What a marvellous idea.

The Periodic Table (1975) is a collection of illustratively written autobiographical essays about the authors triumphs, tribulations, and ordinary events that took place in Italy: before, during, and after WWII.

Primo Levi (1919-1987) was an Italian-Jewish chemist and Holocaust survivor. In an originale manner he narrates the story of his life mostly through his observations and interactions with people, his evolving profession, and environment by which he was surrounded.

The book also includes two fictional tales, each named by a certain element too, but embodied in alchemical symbolism. He must have written them during the time he needed an escape from the uncomfortable reality. They seem to be a metaphor for Levi's state of emotion (I sensed frustration and regret) and discontent with his personal life and endured discrimination.

I would have liked if some of the stories topics were a bit more intimate. Also, the book did not include the period the author spent in the concentration camp. Although, Levi, mentions in the book that this was done for logical reasons as he wrote about it in two of his other books. But their absence felt like a gap in the periodic table and a break in the timeline. I would highly recommend this book to those interested in chemistry and learning about the Piedmont Jewish community.

Ted

There are so-called inert gases in the air we breathe. They bear curious Greek names of erudite derivation which mean "the New", "the Hidden", "the Inactive", and "the Alien".

Thus begins Primo Levi's book of a score or so mini-memoirs. Each of these is named for one of the elements, thus the name of the book. The elements used are in no particular order – not alphabetical, not by atomic number (the ordering of elements in the periodic table). They range from Argon (the first chapter) to Carbon (the last), from Hydrogen to Uranium, from Nitrogen to Arsenic.

Each of Levi's unnumbered chapters is launched with something about the element used for its name. "Argon" begins with the sentence above, and continues for a rather lengthy paragraph along these lines, ending with "… argon (the Inactive) is present in the air in the considerable proportion of 1 per cent, that is, twenty or thirty times more abundant [by volume] than carbon dioxide, without which there would not be a trace of life on this planet."

But then the next paragraph (in "Argon") begins

The little that I know about my ancestors presents many similarities to these gases. Not all of them were materially inert, for that was not granted them. On the contrary, they were – or had to be – quite active, in order to earn a living and because of a reigning morality that held that "he who does not work does not eat." But there is no doubt that they were inert in their inner spirits, inclined to disinterested speculation, witty discourses, elegant, sophisticated, and gratuitous discussion. It can hardly be by chance that all the deeds attributed to them, though quite various, have in common a touch of the static, an attitude of dignified abstention, of voluntary (or accepted) relegation to the margins of the great river of life. Noble, inert, and rare: their history is quite poor when compared to that of other illustrious Jewish communities in Italy and Europe …

Here ends my newer update to original review, continuing below …

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I read this book several years ago, and every so often see something about it here on GR. Perhaps I will write a real review someday, but I would need to re-read it.

(For a real review of Levi's book here on Goodreads, check out https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...)

Levi is well known as a survivor of Auschwitz, a writer of great talent and great humanity. He died (a probable suicide) in 1987.

I thought what I'd do here is give a link to a recent article in the New Yorker by James Wood. It's basically a Levi retrospective, and (without mentioning the new book at all, unless I missed it in a sentence) presumably written to coincide with The Complete Works of Primo Levi, published about a week ago in three slip-cased volumes, with an Introduction by Toni Morrison.

Wood discusses The Periodic Table extensively in the piece, and also writes movingly of Levi's memoirs, available together in If This Is a Man / The Truce.

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/201...

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Previous review: Ornament of the World

Random review: Classics for Pleasure

Next review: Almost No Memory Lydia Davis

Previous library review: My Brilliant Friend Elena Ferrante

Next library review: The Wine-Dark Sea

Ian

There was an occasion last year when I had to hang around for a few hours in a town about 40 miles from where I live – my car was in for repair. As is my wont, I spent the time in a bookshop, and eventually was there long enough to feel guilty about not buying anything. I’d heard of Primo Levi and of some of his books, so decided to settle on taking this one away.

I found this kind of wonderful. Mainly, it consists of snippets from the author’s life and especially his career as a chemist, with each chapter ingeniously linked to one of the atomic elements. Some of the events described are commonplace (others anything but) but each story forms part of a meditation on life. The quality of the writing is outstanding. I realise of course that I’ve read a translation, so credit to translator Raymond Rosenthal for creating such a superb version of the original. The edition I read was in paperback form, but if I’d had this on my Kindle there would have been so much text highlighted that it might have formed the majority the book.

My only slight reservation was that, along with the autobiographical pieces, the book included 3 fictional short stories. I liked the last chapter, “Carbon” but was bit less taken with the other two stories, “Lead” and “Mercury”. The author more or less tells us what he was trying to achieve with “Lead” and I thought that was OK, but I was a bit less keen on “Mercury”. I would maybe take a half-star off for those aspects, but overall, 4.5 stars rounded up. Deservedly a classic.

Steven

I have to admit as I spent most of my science and chemistry lessons staring out the window daydreaming my knowledge of the Periodic Table sucks, Primo Levi has now changed all that. Using each element to fascinating effect in his own experiences, from the classrooms and studies of his youth through fascist Italy to his capture by the Nazi's and ultimate test of the human spirit to rally and remain mentally strong to survive to tell of the aftermath also. The linking of stories to eponymous elements is in a few cases purely metaphorical — in the opening piece the inertness of Argon represents characteristics of his ancestors, Sephardic Jews in Savoy. Levi worked as a chemist, however, and a thread running through the books is what it is to be a chemist, to wrestle with matter; the connection of the stories with elements is usually quite immediate, though sometimes circumstantial rather than substantial. One thing I learned in the second half of reading, he was a seriously intelligent guy and as a free-lance chemical consultant and problem solver the talk baffled the hell out of me!. The shifts in tone make this stand out from similar writings and each small segment can quickly change your perceptions. An interesting and important piece of true life story telling.

Ian "Marvin" Graye

The Connotations of the Elements

All elements have been named in a more or less arbitrary manner: after people, places or mythological characters.

To those who named them, if not necessarily us, these names had metaphorical connotations. For non-scientists, this significance might be lost in the scientific haze that befuddles us.

One achievement of Primo Levi's novel is to revive the power of the metaphors.

Each element he has chosen represents a person, an experience or a story. Each chapter named after an element assumes both an individual and a collective power.

The collective power resides in the periodic table. The tabular presentation of elements not only identifies each element, but, because of the way it has been structured, it also defines their relationships.

In this way, Levi's periodic table symbolises individuals, families, societies and nations.

A Literate Chemist

Science is the foundation of society, even if most of us have forgotten.

It took a literate chemist capable of striding over the two cultures, scientific and creative, to remind us.

Levi recognised that elements rarely manifest themselves to us in a pure, unadulterated form. They appear in combinations, either as mixtures (such as air) or compound molecules.

It was only in the 17th century that scientists started to devote a lot of effort to distinguishing the elements from each other. They had to be separated. They had to be purified, but only for analytical purposes.

Then, with greater knowledge of their properties, they could be artificially joined as new compounds.

There was no particular functional value in the unadulterated purity of a single element in its own right (apart from any beauty that precious metals like silver and gold might be perceived to have).

Enchantment and Adulteration

Levi reached this conclusion from a scientific point of view. The nature of matter is what is of concern to a scientist or chemist.

Still, he managed to find enchantment in matter and its adulteration. It is the stuff of life. Without adulteration, there would be no life and no diversity.

Bit by bit, over the course of the book, he communicates his enthusiasm, happiness and satisfaction to us. It is the wonder of someone who is truly alive.

Racial Purity

Equally importantly, Levi extended the metaphor of adulteration to the type of social and political discourse that emerged in the time of Fascism.

The German and Italian Fascists were trying to achieve purity of their respective races (Professor Googlewiki informs me that in 1921 Mussolini referred to the Italians as the Mediterranean branch of the Aryan race. He later denounced "Nordicism", although the issue continued to simmer).

They regarded other races, in particular Jews, as threats to racial purity. Jews supposedly adulterated Aryan perfection. They had to be eliminated.

What was missing was a perception of different races as different elements in the periodic table.

The universe does not consist solely of one element. There are numerous elements, and all of them have a role, large or small, in making the particular universe that we inhabit. No one element can be said to adulterate the universe.

Matter and Spirit

Race is a product of matter. The Fascists tried to add weight, ironically a rhetorical mass or gravitas, to their arguments by resorting to the language of spirituality.

They believed that a race, the matter behind the physical manifestation of the race, has a spirit.

However, the spirit, according to Fascism, is superior to and dominates matter. It is the desire to preserve and perpetuate the spirit that motivated the political movement behind Fascism.

To do so, other mass, other spirit had to be perceived as inferior, incorrect, defective, deviant, an impurity, something deserving of elimination.

Just as in metallurgy, ore had to be refined: the target metal had to be separated and the impurities discarded on the mullock heap of life or death.

The Fascist modus operandi was to send Jews to extermination camps. Levi, a Jewish chemist, was fortunate to survive the experience, because of the value of his scientific skills.

Tales of Militant Chemistry

For all the horror that the author experienced and witnessed, his novel is not just a compendium of "tales of militant chemistry".

It is an exercise in tolerance of those who would commit or permit evil, as long as they are prepared to repent. His message is one of forgiveness for those who acknowledge the wrong they did.

The chapters are named after 21 elements. I haven't tried to analyse why each one of these elements was chosen or whether there is any significance in the order.

I'm sure that, if you were prepared to put in the effort, it would be like understanding the structure of Joyce's "Ulysses".

These are a Few of My Favourite Elements

The novel starts with Argon, an inert gas, one incapable of aggregation with other elements. Levi applies it to his Jewish family, although he denies that they were wholly inactive:

"The little that I know about my ancestors presents many similarities to these gases. Not all of them were materially inert...on the contrary, they were - or had to be - quite active, in order to earn a living and because of a reigning morality that held that 'he who does not work shall not eat.' But there is no doubt that they were inert in their inner spirits, inclined to disinterested speculation, witty discourses, elegant, sophisticated, and gratuitous discussion.

"It can hardly be by chance that all the deeds attributed to them, though quite various, have in common a touch of the static, an attitude of dignified abstention, of voluntary (or accepted) relegation to the margins of the great river of life. Noble, inert, and rare: their history is quite poor when compared to that of other illustrious Jewish communities in Italy and Europe...

"They were never much loved or much hated...Nevertheless, a wall of suspicion, of undefined hostility and mockery, must have kept them substantially separated from the rest of the population...As is always the case, the rejection was mutual."

Phosphorus, a rare but vital element, applies to a brief love interest, which never really eventuated because of the war:

"We are not dissatisfied with our choices and with what life has given us, but when we meet we both have a curious and not unpleasant impression (which we have both described to each other several times) that a veil, a breath, a throw of the dice deflected us onto two divergent paths, which were not ours."

Gold is the river Dora, which represents youth, joy, life and friendship (even when it is lost).

The Silver chapter details the reunion of two friends, "two positive heroes," at the 25th anniversary of their graduation:

"Each of us would gather more stories like this one, in which stolid matter manifests a cunning intent upon evil and obstruction."

The name of the element Vanadium derives from the Old Norse "Vanadis", which is one of the variants of the name of the goddess of love, Freya or Freydis (who might also be familiar to W. T. Vollmann fans). It is the chapter in which Levi explores forgiveness and repentance, a way out of the horror of the Holocaust.

This is What Matters

The final chapter is Carbon.

Here, Levi acknowledges that his book is neither a chemical treatise nor an autobiography, except to the extent that, like every other piece of writing, it is "partial and symbolic".

Instead, it is a "micro-history" with a scattering of "sad tatters [and] trophies", both failures and successes.

Yet, this chapter asserts how fundamental to life are atoms, elements of the periodic table. Carbon atoms travel from one form of life to another, from an organic form to an intermediate inorganic form, back to organic life. Carbon atoms travel through time, passing on their characteristics to other matter around them.

The focus of this chapter is elements, atoms, molecules. Chemical energy becomes mechanical energy, and mechanical energy generates heat. "Such is life."

Yet, the great beauty of the novel is that it tells the story of people living, loving, giving birth, parenting, and perpetuating both life and love over the ages.

This is matter. This is what matter does. This is what matters.

The Marvel of Diversity

By the end of the novel, you marvel at humanity and its diversity. You value each and every life. No thing doesn't matter. No life doesn't matter.

The novel subtly encourages you to care. It makes you want to behave like you care. Conversely, you struggle to understand that Fascists might have looked at the same people as we do, and didn't care.

This novel is almost an afterthought to two earlier works by Levi about the Holocaust ("If This Is a Man" and The Truce"). It even leaves gaps where the earlier books would have fit. It houses them, makes a home for them. It is a periodic table into which these other elements fit perfectly.

This novel is rich in its own right, but it invites us to read his other works, to wander around the whole periodic table, one element at a time.

The sense of this man, Primo Levi, who is now no longer with us, makes me want to read his other works, so that, like an atom of carbon, his legacy of vitality, creativity, love and forgiveness, can live on, transcending both his life and his death.

Paul

4.5 stars

This is a collection of short stories, twenty-one in all, each one named after an element of the periodic table. In the UK the Royal Institution has voted it the best science book ever. There is a variety of stories: some are very personal memoirs, a few are fictional, some look at industrial processes and there is a good deal about the nature of words. Sometimes Levi does describe a search for a particular element, but in others he uses the fundamentals of the element for comparative purposes. In Argon he uses its almost complete inertness as a symbol for the marginalisation of his Piedmontese Jewish ancestors.

Levi explains his passion for chemistry and the reasons for his pursuit of it as a career; as always the reasons are complex:

“I have often suspected that, deep down, the motives for my boyhood choice of chemistry were different from the ones I rationalised and repeatedly declared. I became a chemist not (or not only) from a need to understand the world around me; not in reaction to the cloudy dogmas of Fascism; and not in the hope of riches or scientific glory; but to find, or create, an opportunity to exercise my nose.”

Levis also writes well and tells a good story and there is a lyricism to his writing and even humour:

“Zinc, Zinck, zinco: they make tubs out of it for laundry, it is not an element which says much to the imagination, it is grey and its salts are colourless, it is not toxic, nor does it produce striking chromatic reactions; in short, it is a boring metal. It has been known to humanity for two or three centuries, so it is not a veteran covered with glory like copper, nor even one of those newly minted elements which are still surrounded by the glamour of their discovery.”

There is a poignancy to it as well, as when he leaves a job at a nickel mine to go to a lab in Milan, describing his essential belongings:

“..my bike, Rabelais, the Macaronaeae, Moby Dick translated by Pavese, a few other books, my pickaxe, climbing rope, logarithmic ruler, and recorder.”

The most powerful piece in the collection is Vanadium. It is post war and the firm Levi is working for has a query about the quality of some compound being purchased from a firm in Germany. He begins a correspondence with his opposite number. Gradually he realizes that he knows the man, a civilian scientist in the war who worked for the Nazis and he met him in Auschwitz. Levi explores his feelings and reactions to a man who was not unkind to him, but who essentially was a moral coward in the face of evil. The last chapter on carbon could be described as a little sentimental, but I can forgive Levi that.

This isn’t a book about science, although there is plenty of science in it; it’s about humanity and the quirks and idiosyncrasies of everyday life. Levi is a good storyteller expressing human warmth, puzzlement and a sense of justice. A must read.

Cherisa B

A series of 21 short stories based on chemical elements and events or people from the author’s own life. Chronologically, Levi wends his way through school and chemistry training, trying to make a living before and after WW2, and his year as a prisoner in Auschwitz (which he covered beautifully in If This is a Man, which was published years before this work). Unique, engaging, ethereal and humanistic, I loved every story, but Iron and Carbon especially. In Vanadium, he comes across one of the Germans who ran the lab where he worked in the forced labor camp as part of a regular business transaction years later, and they exchange correspondence. Breathtaking.

Chosen as one of the best books in science in the 20th century, it’s so much more. Highly recommended.

Edward

This was a pleasant surprise: not at all the mournful account I had expected. The Periodic Table is Levi’s autobiography told thorough his work; an expression of his love for the chemists’ art and trade, and though the war and holocaust (being inseparable from his life) are part of the story, they not central to it (he wrote about these in more detail in other books, which I have not yet read).

I enjoyed Levi’s light, enthusiastic tone, his intimacy and passion, and the stories themselves, which are a mix of the real and the whimsical. Through these stories Levi hints at a human world filed with as many potential permutations and ways of being as the underlying chemical world; a world where all matter shares a common ontology and a common teleology.

When I was young I had an interest in chemistry, which faded after a year of classes that were preoccupied with esoteric theory and taxonomy. Had I read The Periodic Table during this time in my life, Levi’s impassioned accounts of trial and discovery may have convinced me to persevere.

David Rubenstein

This is a book of memoirs by Italian chemist, Primo Levi. On one level, the book is an autobiography. Each chapter has the name of an element of the periodic table, and the chapter relates some episode in Levi's life that has some relationship to that element.

On another level, the book is about the tragedy of the Holocaust. Primo Levi and his fellow chemists lived through the beginning of the war by pushing the war out of their minds. They saw the war for what it was; they had a fateful attitude, in that they could not do anything about it. But, in 1944 Levi was sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The life expectancy for an inmate at the camp was three months, but Levi defied the odds. He remained alive for 11 months, when the Soviet Army liberated the camp. Perhaps the most poignant chapter is about a post-war meeting he had with one of the German guards at the concentration camp.

This book is written in beautiful prose, on a high aesthetic level. Levi comes across as a gentle soul, but does not wallow in sentimentalism. Much of the book is about his studies and his early jobs as a chemist. His writing about the Holocaust is very matter-of-fact. The book is rather short, and it is not a difficult book to read.