Detail

Title: The Moon and Sixpence ISBN: 9781598185218Published August 1st 2005 by Aegypan (first published April 15th 1919) · Paperback 192 pages

Genre: Fiction, Classics, Art, Literature, Historical, Historical Fiction, Novels, European Literature, British Literature, 20th Century, Literary Fiction, Cultural, France

Must be read

- Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House (The Trump Trilogy #1)

- A Brief History of Time

- The Secret of the Nagas (Shiva Trilogy #2)

- Surviving The Forest

- Follow Me Darkly (Follow Me #1)

- Murder in Old Bombay (Captain Jim Agnihotri #1)

- How to Pronounce Knife: Stories

- Consent

- What Happened To You?: Conversations on Trauma

- The Ex Talk

User Reviews

Ilse

Life isn’t long enough for love and art.

Years ago I read and thoroughly enjoyed W. Somerset Maugham’s Theatre, so when I found a copy of The Moon and Sixpence in the bookcase, it looked the perfect breezy weekend diversion I was looking for before I would embark on the finale of Thomas Mann’ s Doctor Faustus. Imagine my surprise having by chance run into a novel which also turned out to be a Künstlerroman , both novels sketching the development of two men who come to live only for their art, the (fictitious) composer Adrian Leverkühn in Mann’s novel, and Charles Strickland, a painter modelled on Paul Gauguin, in The moon and Sixpence - finding quite a few parallels between both novels.

Apart from narrators cultivating a peculiar friendship with the respective artists and who plead for compassion and understanding for the ordeal of the artists they admired, both novels in some sense have a common view on the Artist, the key – Romantic- belief that one cannot have it both ways, the Artist has to choose between love and art (Maugham makes this belief explicit from the very beginning, his narrator declares that the artist's personality is the most fascinating aspect of his art, however repulsive his character or numerous his flaws ). The outcome of that choice doesn’t have to come as a surprise, as Life isn’t long enough for love and art.While Adrian Leverkühn sorely forsakes love in his pact with the devil in exchange for granting him creative genius, Strickland is portrayed as indifferent to love, abandoning his wife and children for his artistic obsessions, which also have a demonic touch. In both cases their choice will have fatal consequences, at least for others. Both are portrayed as monsters in the sense that they are dedicated artists, whose life is totally devoted to their art and so they display monstrous features, even if only in the eyes of those around them. They both consciously choose a hermit's existence, rejecting commonplace life and participation in society, claiming the freedom to live in an ivory tower for themselves – whether on a farm in Germany or a mansard in Paris (and Tahiti later on). Unlike Charles Strickland, however, Leverkühn is vexed by the monstrous nature of his artistry – Charles Strickland couldn’t bother less.

There are many brilliant reviews and analyses of The Moon and Sixpence to find around here which do great justice to this novel as an outstanding work of literature. Nevertheless I am more on the side of these perspicacious reviews (here and here) which point out its inner contradictions and word astutely some of the impressions the novel left me with, encapsulating what becomes visible once the colours of Maugham’s glowing prose have stopped to bedazzle.

As much as the psychological portrayal of the selfish and obsessed painter is well done – from the little I recall from reading about the life of Gauguin the credibility is supreme (whereas assuaging some of the facts, for instance on his health condition, substituting syphilis by leprosy - it wasn’t the uncouthness, egoism and brutality of artist protagonist Charles Strickland that put me off– after all, haven’t those personality features turned into something one has almost come to expect in the Romantic view on the artist (the contrasts and tension between the ugliness and brutality of the personality versus the beauty he – as the genius is of course a man - pursuits to create)?

It were mostly the rather nauseating generalisations on the nature of women, by Strickland and by almost every character featuring in the novel including the narrator, a writer in who one can recognise Maugham himself which simply baffled me (and made me imagine the narrator/Maugham as an even less likeable person than Strickland/Gauguin, which is quite a feat). At times this misogyny turns so pathetic it becomes rather fascinating – even raking up the discussion if women actually have a soul (which was apparently a non-discussion). So this novel left me puzzled and with plenty of questions buzzing in my mind. What was the status quaestionis with regard to misogyny in 1919? Was Maugham representative for his times, or was it mostly the bitterness because of his personal situation (trapped in loveless marriage while being homosexual) that made him spit out his loathing so viscerally that it came to overcast whatever points he makes on conventionalism and creativity? I hope to find some answers in A Brief History of Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, even if it seems too brief to have the space to mention Maugham.

When reading Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living: A Working Autobiography I almost suspected myself of having turned into a sweet water feminist, as her recurrent blaming of patriarchy didn’t much resonate with me. If one however would feel the need to fuel feminist energy, The Moon and Sixpence would make good material to give to one’s children or simple anyone who thinks feminism has become evident or superfluous nowadays, if only to see where we have come from. It must have been from the moment a co-worker started to sing Girls from the Beastie boys in the nineties (‘girls do the dishes’) I was confronted with something as blatantly misogynist/sexist as this book (admittedly, apart from this forum dedicated to books and some newspapers I read little on the internet and so am only vaguely aware of trolling of women who twitter as happened to Mary Beard).

Just a few examples of statements to savour:

When a woman loves you she's not satisfied until she possesses your soul. Because she's weak, she has a rage for domination, and nothing less will satisfy her.

It requires a female temperament to repeat the same thing three times with unabated zest.

Women are constantly trying to commit suicide for love, but generally they take care not to succeed.

I did not then know the besetting sin of woman, the passion to discuss her private affairs with anyone who is willing to listen.

Women are strange little beasts... You can treat them like dogs, you can beat them till your arm aches, and still they love you. He shrugged his shoulders. Of course, it is one of the most absurd illusions of Christianity that they have souls.... In the end they get you, and you are helpless in their hands. White or brown, they are all the same.

Because women can do nothing except love, they’ve given it a ridiculous importance. They want to persuade us that it’s the whole of life. It’s an insignificant part. I know lust. That’s normal and healthy. Love is a disease. Women are the instruments of my pleasure.

What I had taken for love was no more than the feminine response to caresses and comfort which in the minds of most women passes for it. It is a passive feeling capable of being roused for any object, as the vine can grow on any tree; and the wisdom of the world recognizes its strength when it urges a girl to marry the man who wants her with the assurance that love will follow.

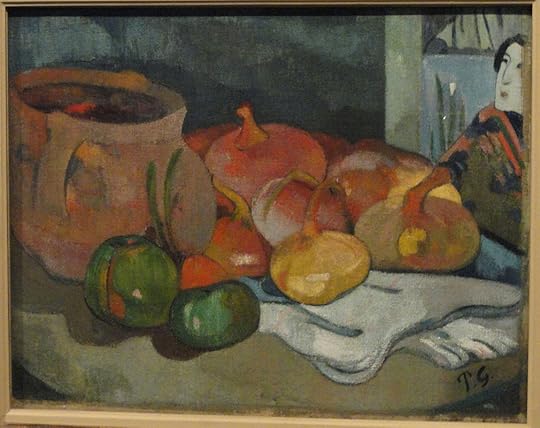

On the plus side, the novel made me look more closely at some of the paintings of Paul Gauguin, which I now appreciate more, particularly the vitality of the colours in his still lives (Gauguin’s painting never particularly spoke to me, I find it particularly hard not to look at his paintings through the lens of an exoticism that reeks of a mythologizing of the noble savage; I admit my not so favourable view on him was also negatively affected by reading this loosely biographical graphic novel some years ago, Gauguin: Off the Beaten Track by Maximilien Le Roy).

Maugham’s novel offers lots of food for thought and could serve as an excellent exercise when one tries to consider a work of art independently from the personality of the creator – whether painter or writer. It made me aware I need more exercise on these issues and so I will definitely read more by Maugham.

Ahmad Sharabiani

The Moon and Sixpence, W. Somerset Maugham

The Moon and Sixpence is a novel by W. Somerset Maugham first published in 1919. The story is in part based on the life of the painter Paul Gauguin.

It is told in episodic form by a first-person narrator, in a series of glimpses into the mind and soul of the central character Charles Strickland, a middle-aged English stockbroker, who abandons his wife and children abruptly to pursue his desire to become an artist.

عنوانهای چاپ شده در ایران: «ماه و شش پشیز (پنی)»؛ «ماه و شش پنی»؛ «قلبِ زن»؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش: روز بیست و چهارم ماه دسامبر سال1970میلادی، و خوانش با عنوان: «قلب زن در ماه فوریه سال1991میلادی

عنوان: ماه و شش پشیز (پنی)؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ مترجم پرویز داریوش؛ تهران، انتشارات پیروز، سال1333؛ در263ص؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، امیرکبیر، سال1344؛ در263ص؛ چاپ دیگر اصفهان، زمان نو، سال1362؛ در334ص؛ چاپ دیگر: تهران، اساطیر، سال1370؛ در355ص؛ چاپ دوم سال1376؛ چاپ سوم سال1388؛ شابک9789645960108؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان بریتانیا - سده20م

عنوان: ماه و شش پنی؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ مترجم: الهه مرعشی؛ تهران، فرهنگ جاوی، سال1393؛ در284ص؛ شابک9786006182216؛

عنوان: قلب زن؛ نویسنده: ویلیام سامرست موآم؛ مترجم: حسین بدلزاده؛ رشت، انتشارات روزنامه سایبان، سال1336، در220ص؛

رویدادهای این داستان پرورده ی خیال نیست بلکه از یادمانها و دیدارهای نویسنده در جزایر جنوب الهام یافته است؛ «چارلز استریکلاند» قهرمان داستان، همان «پل گوگن» نقاش نامدار فرانسه است که «موام» با قلم توانا و سحر انگیز خود شرح زندگانی عجیب توام با عشق و سراسر ماجرای او را به رشته نگارش درآورده اند؛ در این داستان «ویلیام سامرست موام» آنچه را که در قلبِ زن میگذرد، مورد واکاوی و بررسی قرار داده، و جلوه های آن را در زمانهای گوناگون، هنگامی که بر سر لطف و وفا است، و یا آن زمان که دستخوش خشم و کینه است، با مهارت شگفت انگیزی بازنگاری کرده است؛ «ماه و شش پشیز (پنی)» را، «سامرست موام»، براساس زندگی «پل گوگن» نقاش، نگاشته اند، و با ترجمه زنده یاد «پرویز داریوش» به زیور نشر آراسته شده، در کتاب «قلبِ زن» که عنوان فارسی دیگری برای همین کتاب، «ماه و شش پشیز» است؛ پس از مقدمه ها از مترجم و نویسنده؛ فصل نخست کتاب با عنوان: «در محفل ادبی»، چنین آغاز میشود (هنگامی که اولین داستان خود «جنون عشق» را که خوشبختانه سر و صدای زیادی در محافل ادبی برانگیخت نوشتم؛ جوان بودم ...)؛ پایان نقل؛

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 11/02/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ 24/10/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی

Steven

W. Somerset Maugham's Charles Strickland might not be heading onto my list of the most likeable characters in literature, but one thing is for sure, he is certainly one of the most memorable. Strickland, a bourgeois city gent living in London has a dull, soulless exterior that conceals the fact he just may be a genius. He devotes himself to himself, and hides within him a passion for painting that no one else seems to knows about. He doesn't give a stuff about anybody, including his family, and his wife is left baffled when Charles suddenly travels to Paris (and then later on Tahiti) with no intentions to ever come back. She believes he has run away with another woman, but the truth leaves her totally perplexed, after the narrator of Maugham's novel is sent after him, having only meet Strickland briefly before.

Derived from the life of Paul Gauguin, our main character is a man insensible to ordinary human relations, who lives the life of pure selfishness which is sometimes supposed to produce great art, which has always had its fascination for novelists inspired only by the unusual. Accordingly there have been novels in plenty depicting the conflict of the abominable genius with the uncongenial environment, and Mr. Maugham has followed a recognised convention in this story of an imaginary artist of posthumous greatness. He treats him throughout with mock respect, and surrounds his affairs with contributory detail. Maugham's story takes a respectable man who deserts his wife after seventeen years of marriage to get fully behind a great idea - to turn himself into a famous artist, having previously had no experience. His break is succeeded by living destitute with a stubborn determination, and by long periods of work and outbursts of savage behaviour.

Now, here's the thing, does Maugham convince us that Strickland is a real man and a real artist with which we can absorb his traits as part of the essential human creature who lives eternally by his work? It seems he does not. Where every detail should be pungently real, one is constantly checked in belief by the sense of a calculated and heightened effect, and by the passion of Maugham for his subject. Such a passion is sometimes defeated by it's object. Here one is repelled, not so much by Strickland's monosyllabic callousness, but by the knowledge that this callousness is seen and represented without subtlety. This does eventually change towards the end, but what I liked about Maugham's narrative is he never succumbs to the obvious temptation to seek to explain Strickland’s actions to us, we are left in the dark to his motives just like the other characters. Another positive is that he uses the minor elements in the story with an extremely effective manner. There are deeper themes going on here, if you dig hard enough.

The novel is one of a destructive nature, and presents a really terrible philosophy on Modernism which it propounds, but I found it compulsively readable. Maugham’s writing manages to be both powerful and austere, with not a moment wasted. I particularly liked the first-person narrative voice, which captured me with a mix of admiration and disdain for Strickland, something that Maugham struck a masterful balance with.

Luís

I liked the writing and the story; maybe I'm not on the right track, but I take away that everyone deep down can hope for something else, a changing total of his life. Still, it will be too excessive if he does it too late; it will be too extreme (this is happening here). I think this man had taken by his passion, which undoubtedly devoured him before, but he could not express remorse for not doing so earlier. It was a form of guilt that he left behind him, hence this way of life, this violence in his relations with society and others and a destroying state.

This husband offered nothing flattering for a woman trying to find a place for herself in the world of letters and the arts. Nothing salient saved from the banality this character certainly irreproachable but hopelessly ordinary.

One day, however, the insignificant Charles Strickland abandons his wife and home, leaves for Paris, begins a career as a painter, and reveals himself to be an enigmatic, fanciful and sometimes odious being.

Misogynist, cruel to himself and others, he sacrifices everything to work doomed to the incomprehension of contemporaries, treating with equal contempt those who love him and those who hate him, exercising an inexplicable fascination on all.

Seduced less by the artist than by the man, the author draws a portrait of this character that the banality of the surrounding characters makes even more strange.

The delicacy of writing and the conciseness of exemplary anecdotes give the novel an allure of worldliness and oddity that perfectly fits the subject.

Rowena

"Art is a manifestation of emotion, and emotion speaks a language that all may understand."- W. Somerset Maugham, The Moon and Sixpence

I'd only ever read one Maugham before this ("Of Human Bondage") but even with just that one read I could tell Maugham was a very special writer and destined to be one of my favourites. I picked up this thin book thinking it would be a quick, simple read, but I wasn't prepared for the depth and profundity in it. There is a lot going on in this little book, lots to think about.

Reading the back of the book you'll know that the main character in this book, Charles Strickland, was modelled after Paul Gauguin. There's no way I would have guessed that for most of the book, until Strickland/Gauguin moved to Tahiti.Even without knowing much about Gauguin's life, this book was interesting as it took us on a tour of his life, done by a narrator who operates as an unofficial biographer, taking us through Strickland/Gauguin's life from England to Paris, and finally Tahiti.

Strickland is an awful person and extremely misogynistic. It's been a while since I've read such an odious character in literature. I despised him:

"He was a man without any conception of gratitude. He had no compassion. The emotions common to most of us simply did not exist in him, and it was as absurd to blame him for not feeling them as for blaming the tiger because he is fierce and cruel."

It was surprising to witness how the passion in Strickland seemed to remain dormant for years but eventually caused him to act like a man possessed and completely re-evaluate his life as that passion needed an outlet:

"That must be the story of innumerable couples, and the pattern of life it offers has a homely grace. It reminds you of a placid rivulet, meandering smoothly through green pastures and shaded by pleasant trees, till at last it falls into the vasty sea; but the sea is so calm, so silent, so indifferent, that you are troubled suddenly by a vague uneasiness. Perhaps it is only by a kink in my nature, strong in me even in those days, that I felt in such an existence, the share of the great majority, something amiss. I recognised its social values, I saw its ordered happiness, but a fever in my blood asked for a wilder course. There seemed to me something alarming in such easy delights. In my heart was a desire to live more dangerously. I was not unprepared for jagged rocks and treacherous shoals if I could only have change -- change and the excitement of the unforeseen."

Gauguin comes up a lot in discussions on primitivism and orientalism, and reading up on his time in Tahiti really leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. The discussion on place and how we might be searching for a place where we are free to be really spoke to me, but Gauguin being himself meant taking child brides in the tropics, and that reminded me of the fact that Europeans had/have free reign in some parts of the world all due to their perceived power. But still, the idea that we can be perceived differently in different areas, and therefore be more suited to one area than another, is interesting:

"I have an idea that some men are born out of their due place. Accident has cast them amid certain surroundings, but they have always a nostalgia for a home they know not. They are strangers in their birthplace, and the leafy lanes they have known from childhood or the populous streets in which they have played, remain but a place of passage. They may spend their whole lives aliens among their kindred and remain aloof among the only scenes they have ever known. Perhaps it is this sense of strangeness that sends men far and wide in the search for something permanent, to which they may attach themselves. Perhaps some deep-rooted atavism urges the wanderer back to lands which his ancestors left in the dim beginnings of history. Sometimes a man hits upon a place to which he mysteriously feels that he belongs. Here is the home he sought, and he will settle amid scenes that he has never seen before, among men he has never known, as though they were familiar to him from his birth. Here at last he finds rest."

It's hard to summarize this book without bringing up the racist language. There were quite a few racial epithets which, I'm not sure spoke of Maugham's insensitivity to different races, or just that he was reflecting the language and sentiments of the time. Either way, they were shocking, and I could have done without them.

Georgia Scott

Remember your first taste of beer as a kid? Sour, not sweet like a soft drink, it was hard to swallow. Still you tried. That was me reading The Moon and Sixpence. I hated Strickland, the stockbroker turned painter who deserts his wife and children to go off to Paris and Tahiti. His every word was repellent as a bubbly drink going up my nose.

But something told me not to give away or sell my copy. It waited on a shelf up high. Then, today, I read it again the way you do. Dipping in here and there. And that did it. I knew why I still gave it a home.

Free of caring what anyone thinks of him, Strickland is a Bartleby. He knows his life's course and will follow it. Explanations are justifications and he is not offering any. Yet, unlike Melville's "scrivener" whose only words are "I would prefer not to," Maugham's protagonist tells us what he does prefer to do. "I want to paint," he repeats. "I've got to." In these words Strickland speaks for every artist whether the painter, writer, composer, or actor. He speaks for us in our compulsion to create because it is breath itself. Like Strickland, we've "got to" and must embrace our audacity.

"The greatness of Charles Strickland was authentic," Maugham decides. "He disturbs and arrests." Whether successful in our lifetimes or after our deaths, artists who pursue their "got to" drive are an unsettling bunch. So, expect it to be an unsettling read.

Strickland isn't a Shirley Valentine running off to a Greek island to escape the doldrums of life not to mention rain in Liverpool. Strickland is monstrous. I liked his Dutch friend better. But the brush goes to Strickland if I had to choose. I'd toss it like a lifeline to the drowning genius and shout "Catch!"

Jeff

“Beauty is something wonderful and strange that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world in the torment of his soul. And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it. To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist. It is a melody that he sings to you, and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and sensitiveness and imagination.”

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

In addition to plenty of witty bon mots, Maugham dropped several lengthy quotes on the nature of beauty and how relative it is, especially through the eyes of the artist. Maugham’s protagonist, Charles Strickland grows indifferent to pretty much everything in his life: wife, children, luxury, polite society and focuses his passions like a laser on the creation of a vision that’s perceptible to pretty much only him. Few others see it, but Strickland doesn’t care; he’s too focused on the creative process to pay anyone any mind. He’s kind of a brute, who can only articulate his inner perception on the canvas.

Strickland’s a complete ass, losing pretty much all sense of propriety, not caring whether he’s mortally offended anyone who’s willing to lend him a hand, biting that hand with a furious chomp – leaving broken lives in his wake. The further he runs from society (to Tahiti – “a magical place”) and it’s distractions, the closer he comes to being able to extract his conception of “pure” beauty from the dark recesses of his mind.

I’ve known people like Strickland – talented, brilliant, corrosive – people who have that weird light surrounding themselves. Friends and family that have been taken advantage of, cheated, hurt, yet still can’t shake being in the presence of this person; it’s like having one foot in a tornado. The narrator, a writer, who’s been offended by Strickland on numerous occasions still comes around for the proverbial bitch slap. Strickland doesn’t achieve success and recognition until after he’s dead, his family willing to whitewash his transgressions, something that probably wouldn’t surprise or bother him.

The only other Maugham I’ve ever read is The Razor's Edge, that one was a passable read with the same format (first person narrative observer, main character in search of some sort of truth), but this book has a kinetic energy and spirit. You might loathe Strickland and want to throat punch him, but you still have a deep unspoken understanding of his motivations, that although you don’t fully condone, you still respect his vision.

Buddy Read with the artsy, occult branch of the Pantsless Legion of Indecency: Ginger, Kristin, and Stepheny.

Fergus

This book marked a sudden seismic shock in my fractured life.

Reeling from burnout - but finally having swept up the badly burned scrambled eggs that were my brains from off the floor - I hastened with Dante Alighieri into Hades Proper.

It was one of my first Amazon orders after reaching the summit of full retirement.

Having paid off the mortgage and outstanding debts at retirement, I suddenly realized that once again - for the first time in twenty years - we had a decent disposable income.

But it was a tarnished freedom.

I say tarnished, because the hitherto hidden inner lives of folks in my extensive environs were now becoming readily apparent on our peripatetic rounds throughout it.

And with this book, Minos curled his black and smoky tail to show me which Circles of Hell I must now navigate to find a penultimate modicum of tranquility out of it all.

That Peace was long in coming.

But it was worth it.

But my first retirement self-assignment, the Moon and Sixpence - for Fate was calling the shots - flung me into the flames!

For this thinly-veiled Roman a-clef is a portrait of that (Beautiful? You’ll see!) painter Paul Gauguin.

And Maugham goes Wilde with his brushwork, creating a Picture of Dorian Gray outa Gauguin’s Real-Life tarnished Personality!

Read it if you dare.

You know, sometimes we see all the bright colours of our life fade into the drab street talk of low-level mediocrity...

And if you’re as sensitive as me -

It could TRANSMOGRIFY your worldview:

And begin your own Spiritual Journey toward the Freedom of Peace.

Henry Avila

How much do we forgive a great, talented artist who is also a despicable human being? Will his admirers look the other way, thinking since he is no longer around and no more harm can be done by him, it is all right now to forgive and forget, besides he didn't do anything to their family but to other people...Shakespeare said, "The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones"... Englishman Charles Strickland a thinly disguised Paul Gauguin, is one of those men, selfish, cruel, disloyal an unfeeling cad you would loathe if you had ever met, nothing matters but his art, everyone else he can and does step on to reach his higher calling, being a superb painter yet nobody believes in his abilities, they see only a primitive man with the same tendencies on canvas, besides there are hundreds of better painters in Paris. Strickland had abandoned his wife and two children in London, leaving his family without any means of support if they starved he wouldn't care, nothing is really important but his destiny, set at the turn of the 20th century, Somerset Maugham does not try to hide the fact that he is the person narrating this novel. Having briefly met Strickland in London when the future legend was just another boring, ordinary, nonentity a monosyllabic stockbroker, who could guess of his later fame. Maugham is more impressed by the charming Mrs.Strickland though not pretty, she does radiate what the perfect Englishwoman should be in that era. Later the shocked lady embraces the rumors that her husband had fled with a young shopgirl to France , she could not face the truth which would be humiliating....Mr. Strickland had secretly gone because he needed to paint. In Paris living in squalor in an one room, filthy, pungent, airless apartment he ekes out a living by guiding curious Englishmen, to the sordid sections of the city that no respectable person would go, the kind of areas policemen hate foreigners to see. This or any other jobs which puts money in his hands, more so for buying things to continue painting than to eat or pay the rent, he has lost much weight to rather an unhealthy level . None buys his paintings however he doesn't care. Finally meeting a bad Dutch painter the humane Dirt Stroeve, who actually sells his mediocre paintings, short, plumb, gregarious he never takes it personally when fellow artists disparage his product. Still his English wife Blanche does, she has a checkered past and this type of woman can't forgive the man that saved her, Dirt. An ailing Strickland becomes dangerously ill, he is nursed by the generous Dutchman, the only person who perceives his genius in is own home, the reluctant wife helps, the life of this scoundrel will not end here, he pays back his huge debt by taking away his Blanche ... Maugham is now living in Paris, and becomes friends with the always kindly Dirt, writing a play there, is more upset than her husband, he will forgive if she returns... but tragedy ensues. Strickland somehow gets on a ship and after much travels arrives in the beautiful, tropical, south seas island of Tahiti...Years pass, nothing is heard about this fugitive from civilization until during WWI, Somerset Maugham at his government's request, goes to the same island that Strickland was on, there the paintings he had been indifferent to shocks his senses, the sparkling, plethora of colors, the blues, greens, yellows, reds, violets, and whites, bright, brilliant, a glorious stream of unending shades it teases the mind and makes him dizzy, this, never captured before so well on canvas...now he has seen the real Strickland.

Ahmad Sharabiani

The Moon and Sixpence, W. Somerset Maugham

The Moon and Sixpence is a novel by W. Somerset Maugham first published in 1919. It is told in episodic form by a first-person narrator, in a series of glimpses into the mind and soul of the central character Charles Strickland, a middle-aged English stockbroker, who abandons his wife and children abruptly to pursue his desire to become an artist. The story is in part based on the life of the painter Paul Gauguin.

عنوانها: ماه و شش پشیز (پنی)؛ ماه و شش پنی؛ قلب زن؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش: بیست و چهارم ماه دسامبر سال 1970 میلادی و در ماه فوریه سال 1991 میلادی

عنوان: ماه و شش پشیز (پنی)؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ مترجم: پرویز داریوش؛ تهران، انتشارات پیروز، 1333؛ در 263 ص؛ چاپ دیگر: تهران، امیرکبیر، 1344؛ در 263 ص؛ چاپ دیگر: اصفهان، زمان نو، 1362؛ در 334 ص؛ چاپ دیگر: تهران، اساطیر، 1370؛ در 355 ص؛ چاپ دوم 1376؛ چاپ سوم 1388؛ شابک: 9789645960108؛

عنوان: ماه و شش پنی؛ نویسنده: سامرست موام؛ مترجم: الهه مرعشی؛ تهران، فرهنگ جاوی، 1393؛ در 284 ص؛ شابک: 9786006182216؛

عنوان: قلب زن؛ نویسنده: ویلیام سامرست موآم؛ مترجم: حسین بدلزاده؛ رشت، انتشارات روزنامه سایبان، 1336، در 220 ص؛

ماه و شش پشیز (پنی) را سامرست موام براساس زندگی پل گوگن نقاش نگاشته و نخستین بار با ترجمه زنده یاد پرویز داریوش به زیور نشر آراسته شده بسیار خواندنی ست. ا. شربیانی

Steven Fisher

“Beauty is something wonderful and strange that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world in the torment of his soul. And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it. To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist. It is a melody that he sings to you, and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and sensitiveness and imagination.”

Mary

We want the world. We want it all. We want the moon. And still it's not enough.

It's my long term goal to read everything Maguham wrote, a goal that I doubt will be very difficult to reach. He writes with such poignant observation and wit and in The Moon and Sixpence he captures the all encompassing, obsessive and brutal nature that perhaps it takes to be an artist.

Told by an unnamed narrator, we are introduced to Charles Strickland, a beastly yet seemingly ordinary man who one day leaves his wife, his children, his job and his entire life to paint. The drive to create is all there is in him, and leaving a trail of destruction he goes to Paris (don't they all?) and then to Tahiti. He is displaced, disassociated and curiously unappealing. It is a wonderful and extreme portrait of the innate need some have to follow their calling, or better still, the lack of choice they have to do so.

I have an idea that some men are born out of their due place. Accident has cast them amid certain surroundings, but they have always a nostalgia for a home they know not. They are strangers in their birthplace,and the leafy lanes they have known from childhood or the populous streets in which they played, remain but a place of passage. They may spend their whole lives aliens among their kindred and remain aloof among the only scenes they have ever known. Perhaps it is this sense of strangeness that send men far and wide in search for something permanent, to which they may attach themselves. (p.135)

Sara (taking a break)

It must be said up front that I am a huge fan of Maugham. I like his writing style, which always makes me feel as if I am sitting with a friend and he is telling me about someone he actually knows. With this conversational tone, Maugham leads you into the depths of the human soul and sometimes leaves you to find your own way out.

Based very loosely on the life of Paul Gauguin, this novel is a study in how much a true artist will do for the sake of his art: not only how much he will endure, but how much he will inflict upon others. You cannot like Maugham's character, Strickland, nor, I think, can you truly understand him. Even our narrator never manages to understand the man, and he has been observing him for a lifetime. I can't help wondering how much Maugham felt that he was, himself, a man who had to follow his art at any cost. Of course, for Strickland and anyone who happens to come too close to him, the costs are extreme.

One of the important questions Maugham raises in this novel is what makes up success and who gets to decide if you are successful. Is it truly about how much you acquire outwardly or how much you acquire inwardly?

"I wondered if Abraham really had made a hash of life. Is to do what you want, to live under the conditions that please you, in peace with yourself, to make a hash of life; and is it success to be an eminent surgeon with ten thousand a year and a beautiful wife? I suppose it depends on what meaning you attach to life, the claim which you acknowledge to society, and the claim of the individual."

I think Maugham thought that we too often attach the wrong meaning to life, that we strive too often for what others tell us should be our want instead of the things that our soul cries out for in the night. None of us wishes to be Strickland. Hell, we don't even want to know Strickland, but each of us is faced with his same choice--cut our own path or follow the dictates of society--and too often we make the wrong decision.

Nenia ✨ I yeet my books back and forth ✨ Campbell

Instagram || Twitter || Facebook || Amazon || Pinterest

I'm working my way through an omnibus edition of Maugham's work, and man, he can write. I'm torn between the impulse to swim leisurely through his prose or just gleefully cannonball into it. Unlike some writers of this time, Maugham is not particularly flowery, but he has an interesting way of presenting ideas and constructing sentences that makes you want to read over them several times, just to appreciate their ideas and form.

MOON AND SIXPENCE, which could just as easily be called "Portrait of the Artist as a Douche," is based loosely off the life of the artist, Paul Gauguin. I tried to pronounce his name several times, ineffectively, ranging from gewgaw, to Google, to gaijin. As it turns out, the way it's actually pronounced makes him sound like a creature from a Japanese monster movie (it rhymes with "Rodan"), which is only the first way this book surprised me.

Strickland seems like he has the ideal of the moderately successful life: a wife, children, a good job with steady pay. But he is discontent, and one day, coldly decides to leave his wife and job and go to Paris, living in squalor. Why? So he can paint. The confusion of his family, neighbors, and the narrator himself is palpable. To paint? Not because of madness, or because of another woman - but just... for art? For art's sake, and not for fame?

The narrator follows Strickland, as he wrecks yet another marriage, paints more art, and eventually goes to Tahiti, where he finds the climate agreeable and even obtains one of the locals as a "wife." The whole time he is cruel and scornful, dismissive of others' feelings, wants, or desires, and even his own comfort. Everything must be sacrificed for art. Ultimately, I'd say this is a tragedy, because that vision ends up consuming Strickland; he pours his entire being into his art, and like many artists, it isn't until he's dead that his work becomes first a curiosity and then something far more powerful.

A lot of my friends did not enjoy this book and I can certainly see why. Strickland is a jerk, and so is the narrator. There's a casually dismissive attitude towards the things that people generally consider worthy in a human being: compassion, empathy, loyalty, family, kindness, charity, etc. Art here is portrayed as something wholly selfish, and the message here seems to be that it is somehow okay; that an artist is allowed to be an egotist, because self-absorption is necessary for introspection. I don't like that message, so I can see why some people might write off MOON AND SIXPENCE as too dark and grim and irritating. However, I found myself fascinated by these terrible characters.

I enjoyed this book a lot. I've read Maugham before and really liked his work, so this isn't really surprising. His other book was more of a comedy of manners, though; it was nothing like this. I'm really looking forward to working my way through his repertoire and seeing how his stories vary, while enjoying his beautiful writing and compelling, yet flawed characters.

4 stars

Krista

It’s a preposterous attempt to live only for yourself and by yourself. Sooner or later you’ll be ill and tired and old, and then you’ll crawl back into the herd. Won’t you be ashamed when you feel in your heart the desire for comfort and sympathy? You’re trying an impossible thing. Sooner or later the human being in you will yearn for the common bonds of humanity.

I want to start with a note on the title (which does not appear in the novel). Apparently, a reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement wrote of W. Somerset Maugham's Of Human Bondage that its protagonist was "so busy yearning for the moon that he never saw the sixpence at his feet”. I haven’t read any other Maugham, but this must be a common theme for him (if he reused the phrase as the title of this, his next book) and this quote about yearning “for the common bonds of humanity” seems to hearken back to “of human bondage” (making me think that Maugham wanted the reader to consider these novels together and I had a pleasantly informative time googling about Maugham and his writing and Gaugin and his art.) To the review proper:

Each one of us is alone in the world. He is shut in a tower of brass, and can communicate with his fellows only by signs, and the signs have no common value, so that their sense is vague and uncertain. We seek pitifully to convey to others the treasures of our heart, but they have not the power to accept them, and so we go lonely, side by side but not together, unable to know our fellows and unknown by them. We are like people living in a country whose language they know so little that, with all manner of beautiful and profound things to say, they are condemned to the banalities of the conversation manual. Their brain is seething with ideas, and they can only tell you that the umbrella of the gardener's aunt is in the house.

Loosely based on the life of Paul Gaugin, The Moon and Sixpence has a narrator (whose life experiences are broadly those of Maugham himself) who finds himself crossing the path of a misanthropic painter over the course of his hermetic and uncelebrated career. I liked that the narrator only reports known facts — his own conversations with this Charles Strickland or conversations that he had with others about the man — and I liked the irony of him saying that if this were a novel he’d imagine a childhood backstory to explain the man’s prickly personality, or his apologies that he needed to invent dialogue for Strickland because so much of what the artist conveyed was in grunts and gestures. I don’t know if this was a common concept in 1919, but everything about the narrator (even quoting from invented biographies of Strickland) trying to add to the body of knowledge about a genius painter who wasn’t appreciated until after his death felt fresh and modern. As Strickland had left his job as a London stockbroker and abandoned his wife and children, at the age of forty, to pursue his painting, the question at the heart of this novel is: Does genius alone excuse a man for throwing off the bonds of humanity in order to pursue his passions outside the bounds of society? (As Maugham himself left his wife and child to explore the world with his gentleman companion/secretary/lover — travelling from Paris to Tahiti in the footsteps of Gaugin — he seems to be making the case for his own life as much as the painter’s; when Maugham writes about “artists”, he is obviously including himself.)

Why should you think that beauty, which is the most precious thing in the world, lies like a stone on the beach for the careless passer-by to pick up idly? Beauty is something wonderful and strange that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world in the torment of his soul. And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it. To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist. It is a melody that he sings to you, and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and sensitiveness and imagination.

As much as the concept felt modern, the attitudes were very much of their time, with offputting racism, classism, and frequent misogyny. (It is not incidental that I wrote the question is about a man’s right to pursue his passions; Maugham [or at any rate, his narrator] does not seem to like the ladies very much.) Some representative passages:

• I have always been a little disconcerted by the passion women have for behaving beautifully at the death-bed of those they love. Sometimes it seems as if they grudge the longevity which postpones their chance of an effective scene.

• Women are constantly trying to commit suicide for love, but generally they take care not to succeed.

• “Women are strange little beasts,” he said to Dr. Coutras. “You can treat them like dogs, you can beat them till your arm aches, and still they love you.” He shrugged his shoulders. “Of course, it is one of the most absurd illusions of Christianity that they have souls.”

(Perhaps even in 1919 the idea of Gaugin taking a thirteen year old Tahitian wife, while still married, was creepy; in this novel, Strickland’s bride is seventeen. Better?) From people not understanding Strickland's painting within his lifetime (such that he was always just one step ahead of starvation) to people kicking themselves for not buying up his work cheaply when they were deemed priceless masterpieces after his death, the point can be made that the genius was always present in the work; the pursuit of truth and beauty is its own reward, separate from the opinions of others:

The moral I draw is the artist should seek his reward in the pleasure of his work and in the release of the burden of his thought; and, indifferent to aught else, care nothing for praise or censure, failure or success.

Back to the title: Perhaps the true lesson is to support those who would ignore the sixpence at their feet in pursuit of the moon. This was a very compelling read (even if the racist bits were totally offputting) and I am interested in reading more from Maugham.