Must be read

- The Power of Myth (Joseph Campbell and Power of Myth)

- For the Love of Armin

- Hometown Girl Again (Hometown #5)

- If I Stay (If I Stay #1)

- Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers

- Famous (Quantum #8)

- She's Come Undone

- Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age

- Exodus (The Ravenhood #2)

- The Bridge Kingdom (The Bridge Kingdom #1)

User Reviews

Ian "Marvin" Graye

Anagnorisis

Structurally, "The White Hotel" resembles Nabokov's "Pale Fire", while stylistically it has more in common with Thomas Mann's "The Magic Mountain".

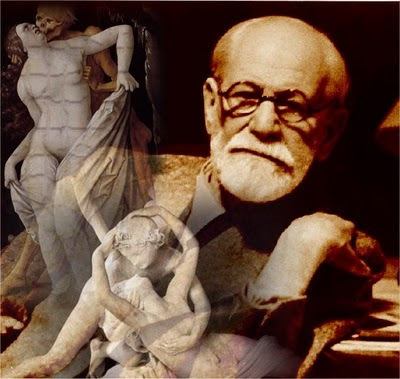

There are two main differences from Nabokov’s novel: the relative lack of metafictional self-reflexiveness in "The White Hotel", and D. M. Thomas' respect for Freud, whereas Nabokov says he detests him:

"I think he's crude, I think he's medieval, and I don't want an elderly gentleman from Vienna with an umbrella inflicting his dreams upon me. I don't have the dreams that he discusses in his books. I don't see umbrellas in my dreams. Or balloons.

"I think that the creative artist is an exile in his study, in his bedroom, in the circle of his lamplight. He's quite alone there; he's the lone wolf. As soon as he's together with somebody else he shares his secret, he shares his mystery, he shares his God with somebody else."

From Bad Gastein to Babi Yar, and Onwards to Heaven

If you count the prologue, "The White Hotel" is divided into seven sections:

* the prologue - an exchange of letters to, by and about Freud;

* an exuberant twelve page poem (what Freud describes as "pornographic and nonsensical...doggerel verse") ostensibly written by the Jewish opera singer Lisa Erdman;

* a journal supposedly written by Lisa about her stay in the spa Bad Gastein ("If I'm not thinking about sex, I'm thinking about death. Sometimes both at the same time.");

* a Freudian case study about the analysis of the pseudonymous Frau Anna G. (actually Lisa) - the style is that of Freud, and shows what an exceptional literary writer Freud was (whether or not you agree with the foundations of psychoanalysis);

* a third person narrative about Lisa;

* another narrative about Lisa’s adopted son, Kolya, which describes the Holocaustic events at Babi Yar in Kiev in 1941; and

* an hallucinatory, almost magic realist account of Lisa’s apparent arrival in Palestine/Heaven ("The Camp").

From Eros to Thanatos

In a later article, D.M. Thomas describes the novel in overtly Freudian terms:

"I had chosen to encompass the extremes of pleasure and pain, Eros and Thanatos. A young opera singer, Lisa, is analysed by Freud in Vienna, and writes for him what he calls an 'inundation' of violent sexual fantasy. The centrepiece of the novel is his analysis of her. Naturally he traces her hysterical illness back to her childhood; later, it appears that, being half-Jewish, her illness stems from a premonition of the 'real hysteria' of the Holocaust."

A Far Country

Thomas is much more accepting of psychoanalysis than is Nabokov, though he does have Freud write:

"I call to mind a saying of Heraclitus: 'The soul of man is a far country, which cannot be approached or explored.'

"It is not altogether true, I think; but success must depend on a fair harbour opening in the cliffs…

"...the physician has to trust his patient, quite as much as the patient must trust the physician."

Both Freud and Lisa realise that much of the fictional Freud’s psychoanalysis of Frau Anna G. is misguided by Lisa’s dishonesty and evasiveness in session. A fair harbour did not always open in her cliffs. In Nabokovian terms, she did not always reliably share her secrets or her mystery with her analyst (though she does share them with her readers via her sections of the novel, assuming she can be trusted).

"An Erogenous Flood"

The fictitious Freud describes Lisa's writings as "an erogenous flood, an inundation of the irrational and the libidinous...it is as if Venus looked in her mirror and saw the face of Medusa." He regards them and her sessions as of dubious honesty.

The different sections of the novel are not merely juxtaposed, but feed off each other as the truth apparently coheres over time. The truth seems to emerge from Lisa’s hallucination and fantasy.

In the meantime, Thomas has a lot of Nabokovian fun and games with identical twins, dreams, secrets, memories, labyrinths of the heart, trains, umbrellas, childlessness, incest, fear of pregnancy, homosexuality, honeymoons, psychosomatic symptoms, anti-semitism, black cats, crucifixes, fir trees, fires, floods, landslides, storms, mirrors, premonitions, opera, swans, wombs, and wild irrationality.

All Compact

Thomas’ Freud quotes Shakespeare in a context that can equally be applied to the structure of the novel:

"The lunatic, the lover, and the poet,

Are of imagination all compact…"

D. M. Thomas achieves this compact in an equally compact and enjoyable 240 pages that deserve to be exhumed and recognised as a superior work of British post-modernism, even though it’s superficially dressed in the garb of late modernism.

SOUNDTRACK:

Ian McCulloch - "The White Hotel"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-s_a...

The Chills - "The Male Monster from the Id"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XO95i...

Teresa

There's so much I could say about this book, but I haven't strayed into spoiler territory in a review before and I don't want to start now. More than with any novel I can think of that I've read, this is more than a sum of each part. For example, the fictional case history 'written' by the novel's Freud would mean nothing without the previous two sections 'written' by his patient; the same is true of the following sections relating her later life and that of the world at large, each with a Freudian trope of train journeys.

A traumatic incident from the patient's youth is glossed over by the patient herself and then by the fictional Freud, who thinks an earlier event is the key. Nothing is heard of it again and to the reader this seems, glaringly and obviously, wrong. As later events spool out, we realize Freud does not know all about this woman (that would be impossible, especially in this rendering). Her case is compared to that of the real-life Freud's Wolf-Man, which the author of this novel has to know was ultimately not the success Freud thought it to be.

Of course, I knew much about the novel's time period before reading it, yet this literary experience of it has left me helplessly angry, knowing the world was capable of and is still full of this kind of senseless violence. But, even with this residual anger, there is a catharsis to be had due to the author's mystical ending of (Jungian?) individuation.

When we encounter war or crime statistics, we remind ourselves, or I think we should, there was a living, dreaming, thinking, complicated individual behind each and every one of those numbers, but do we really comprehend that fact? This novel helps us to do that in all its horror and glory.

Jennie

Really scandalous book that blends eroticism with violence and psychology to portray the horrors of the Holocaust. My English major roommate recommended it to me as his favorite book when I was working on my undergrad. After the first few chapters I was a little disturbed for him, haha. But when I reached the end I realized the powerful effect of the White Hotel. Entrancing, hypnotic, outrageous and multi-layered, this is a book you will not soon forget.

Sally

Well, that was weird.

It went from intensely sexual, to clinical, to narrative, to horrific, to just plain bizarre.

Spoiler: I think this might be a spoiler, but I wasn't exactly sure what was going on for the last 20 pages, so it might not be. It seemed like everyone was in heaven, or some kind of after-world, and the protagonist (I use that term veeeeeeeeeeery loosely) and her mother were taking a walk while reuniting and talking about a threesome witnessed by the child protagonist of her mother, mother's twin sister, and mother's sister's husband. The protagonist gets tired, dizzy, and so she and her mother decide to take a sit down to rest. The mother whips out her mammary and offers daughter a suckle "to revive" herself. This goes on for about 3/4 a page, and then the mother leans over to suckle from the daughter's breast. Then, both refreshed, they get up and continue with their walk.

This is only one of maybe 8 adult breast-suckling scenes in this book.

And I give it three stars why?

Not for all the breast milk drinking, that's for sure.

Well, there were some really intense passages detailing the confusion of the initial days of the Jewish "relocation" that happened when Germany invaded Kiev. The reader is just as uncertain as the protagonist as the scene unfurls. She wakes early, feeds her son, and heads out with her suitcase full of all her worldly possessions believing they can catch a good seat on the train that will take them to Palestine. Instead they are ... well, I won't go into that.

There was another entire section about the Viennese Opera which seemed to be too brief once it had past. The protagonist is hired from afar to replace Vera, who had fallen and broken her arm (but was also pregnant and couldn't continue through the run of the performance)she receives lukewarm reviews from the Viennese critics, but goes through with the run. This turns out, in retrospect, to be the highlight of her late-started career. Earlier she had been a ballerina, but got pregnant, quit the ballet, and then lost the baby.

Before this section Lisa, in a section confusingly titled "Frau Anna G." relates her dreams and fantasies to Sigmund Freud, who, despite her resistance, analyzes the heck out of her psyche. This goes on and on, and was mostly interesting to me because of last year's lit theory class. Without that background I might have been tempted to skim this section.

Now that I'm finished I would say the entire book reads with the confusion and blur of an old woman looking back on her life. Yet as I passed through each section things appear as though it happening at the time - the young, sexual, passion-filled pages depict the consciousness of that person at that time, for instance. Only later, through psychoanalysis with Freud himself does Anna/Lisa see her lies, her self-betrayals, and what was real vs. what was imagined.

Where in the world did I hear about this book? Well, it has always stuck in my head the scene in Prelude to a Kiss where guy and girl are first meeting one another, and he tells her he's "been reading" The White Hotel and she gets it, gets him, and they fall more in love. I wondered why, what about that book could so clearly define a person's preferences and personal tastes? That movie itself was disconcerting, but elements like that tend to stick in my mind.

So when I found it at a flea market (along with a pristine Michael Jackson Off the Wall LP and Madonna True Blue LP and a VHS copy of A Beautiful Mind) I wanted to give it a go. It took me nearly 9 months to pick it up.

I'm not sorry I read it, but I might not go around talking about it to just anyone either. I feel kind of dirty now.

Daisy

Do not read this book sat in the hairdresser’s chair as I attempted to do on a Saturday afternoon. The opening sections are very sexually graphic, in fact they comprise of nothing but sexually graphic scenes. It’s the literary equivalent of a YouPorn best bits compilation and like the website it got repetitive and became draining to read. Sex is after all more of a participant than spectator sport.

We have the opening poem and then a journal that the poem is based on. Both written by Anna G (a pseudonym given his patient by Freud) they tell of a woman nearing 30 who meets a young man on a train has sex with him and then find a hotel (the titular White Hotel) together where they spend several days having sex in all permutations often in public. Despite it being labelled a journal one can tell it is purely the stuff of dreams and fantasy as it recounts numerous incidents that are beyond the realms of possibility; the frequent and varied disasters that kill of the guests and the mass breast-feeding event that happens in the dining room.

In the following section the strangeness is explained as Anna G is a patient of Freud who seeks help because of her recurrent pain in her left breast and pelvis and her breathlessness. Of course being Freud he suspects hysteria and encourages her to share her dreams which she does in the form of the poem and journal. Freud’s diagnosis is of course around her relationship with her father and her repressed sexuality and, whether or not one believes it is little more than hooey, Anna recovers her health and goes on to marry have a successful career and be as happy as anyone can expect to reasonably be – though the aches and breathlessness never fully disappear.

We then have a section which is more of a traditional novel style telling of Anna’s life and an epistolatory section of her correspondence with Freud. These sections are at odd with their predecessors as they are calm, lightly humorous and more straight-forward storytelling and if it wasn’t for Anna’s sharing that she had a premonition or feeling that Freud’s grandson would die (something she reveals to him on hearing that he has) and Freud’s response that if he had his time over again he would have devoted his life to the study of telepathy.

These seemingly innocuous comments take on momentous proportions when we read the final section. Harrowing and violent and completely unexpected all of the issues Anna takes to Freud are explained. One of the most poignant passages, and one which moved me immeasurably was the description of how even in the midst of the most atrocious horrors some things remain unaware and can even retain their beauty.

The scene became tinted with mauve. She watched cumulus gather on the horizon; saw it break into three, and with continuous changes of shape and colour the clouds started their journey across the sky. They were not aware of what was happening. They thought it was an ordinary day They would have been astonished. The tiny spider running up the blade of grass thought it was a simple, ordinary blade of grass in a field.

A beautiful, brave book that amazed me with the stylistic variation, poetry, journal, report, epistolatory. Read it and lament that writers today lack the vision and bravery of writers of the previous decades (if you want to quibble compare this Booker shortlisted work with the predictable and pedestrian winners of late).

Roger Brunyate

Freud and the Final Solution

[2005] An extraordinary book, historical in its way, yet put together like the movements of a musical composition. Introduced by Sigmund Freud, the book's first three movements consist of the erotic fantasies and case-history of one of his female patients, overlapping, expanding, and gradually turning into almost normal narrative. But then the story takes a different course with the convulsions of the century, and becomes a testament of the Holocaust, harrowing and chillingly authentic. Only at the end does the fantasy element return, pulling together the earlier themes into a kind of benediction. I originally questioned whether the book cohered as a whole, but as it has lingered in my memory I have become aware of structural unities that are entirely satisfying.

I am submitting this review after also reading W. G. Sebald's Austerlitz, another Holocaust novel that stalks its subject from an unexpected angle. It makes me wonder whether, with this subject, the frontal approach of straight narrative is possible any more, but here are two masterpieces that not only succeed brilliantly in their own genre but chart new directions for the modern novel as a whole. Both writers recognize that some events are so powerful as to warp the consciousness of entire generations. While Sebald looks for traces of this trauma like an archaeologist studying past artifacts, Thomas moves in the opposite direction, starting at the beginning of the century, when Freudian psychology made it possible for the first time to trace the rifts in the human psyche that would ultimately lead to such inhumanity.

======

[2017] This was one of the very first reviews I wrote, when I was just beginning on Amazon. Despite many, many other Holocaust-related books I have read since, with a particular interest in what I called "stalking its subject from an unexpected angle," this one still sticks with me as utterly sui generis, and it has remained among the very top of my best books ever. I looked back just now to see if I had done it justice. I certainly conveyed my enthusiasm, but I am surprised too by all I left out that I would have included if writing today: the fact that an entire section of the book is written in verse; the extreme use of pornography in the erotic sections; the wonderful writing about an opera singer; and (looking at it again just now) the proportions, whereby the parts packing the greatest punch (the first and last) are also the shortest.

On the other hand, I now wonder if it is a book that can be reviewed at all without spoilers. Even to put it on my Holocaust shelf is to give away something that Thomas (as I recall) keeps as a complete surprise until the very end. And yet nothing of what I have written above, especially the discussion in the second paragraph, could have been said without it. Perhaps this is a case for hiding the entire review?

Paul Bryant

There's a moment in Ernest Hemingway's novel To Have and Have Not which I thought was a real zinger at the time - we have been following Harry and his wife and their relationship intimately - they have some big financial problems but he loves her, and that's always good when a middle aged guy loves his wife don't you think, so you see her from his point of view. Then later you have a different narrator, some other guy, and he's driving along, maybe on his way to see Harry, and he sees this random woman crossing the road and thinks what an ugly old bag she is, you know, in that gracious way that men think at times, and then suddenly we see that the old broke down woman is Harry's wife, who we had, through Harry's eyes, been thinking of as a beautiful, warm, loving irreplaceable human being - which she was.

The zooming round of perspective is what I loved about that. And the double aspect of reality. It made me dizzy.

In The White Hotel we are blathering away with this boring Freudian stuff about this boring young woman and her sexual neuroses (and roses and roses) and all this maudlin sex fantasty dream crap and then ka-splat she's in the middle of one of the most gruesome Holocaust incidents.

The perspective switch from the intimate, delicate human concern for this young woman expressed in the psychoanalytical part of the book to the terminally disgusting people-as-vermin-to-be-eradicated part was beyond shocking when I read this. It was a literary sucker punch. I didn't see it coming.

Whether big effects is what novels should be aiming for is another matter. But this book certainly delivers its big effect.

K.D. Absolutely

Strange book.

Or maybe I am just not equipped to understand everything.

It is composed of a prologue and 6 chapters in almost different forms and themes: (1) epistolary introducing the main characters; (2) erotic fantasies told in poems; (3) erotic journal in first-person narrative; (4) case history in third-person plain storytelling; (5) clinical psychoanalysis; (6) holocaust; (7) outright bizarre conclusion.

I hate some parts of it not because it is boring but it is hard to understand. I had a 3-unit course in Basic Psychology in college and all I can remember now about Sigmund Freud, which is a fictional character here and who narrated #5 above, is his interpretation of dreams: that dreams are repressed emotions and that if you dream of a snake or anything elongated it means you are longing for a penis and if you dream of a box or anything that resembles a container, is that you want to fuck a pussy. I also remember hearing about Oedipus complex which means any emotions or ideas that we keep in our subconscious. I am sure, there are other brilliant things that Sigmund Freud said but I just forgot or actually did not understand them.

So, if you are a psychology graduate, practitioner or interested on it, this book is for you.

Anyway, I still liked this book basically for D. M. Thomas' strange imagination which is similar to Elias Canetti in his opus Auto-da-Fe especially in #3 and #4. Then the clinical psychoanalysis, being full of medical terms, reminded me of a recent read: Rebecca Skloot's The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. For a while, I thought that I was reading the real life Sigmund Freud (the scientist) only to find out in Wiki that this is 100% fiction and Sigmund Freud (the character here), did not have a similar patient during his life time. Of course, I would be a hypocrite if I say that I did not enjoy #2 and #3 that have all these erotic tales beautifully narrated in prose and poetry. See, it is better, i.e., healthier, to express myself in the open than to hide it in my subconscious thereby adding something to my oedipus complex.

This tells a story of a 29-y/o woman, Anna G./Lisa suffering from acute psychosomatic pain in her left breast and womb and so she consults Sigmund Freud. So, during the course of the treatment, D. M. Thomas gives the background of the woman, her family history, part of which is that burning White Hotel where her adulterous mother got burned while having sex with her uncle. Then of course the harrowing inclusion of her experience during the Holocaust provides a pivotal point later in the story.

Overall, I liked this book but I wish I knew more about Sigmund Freud to appreciate everything so I did not get fixated on the yummy erotic parts ha ha.

Laura

When I attempted to read The White Hotel when it first came out, I was 14 and unable to get through it. I knew there was something much bigger at work but I couldn’t grasp the apparent profundity of the work. Now, at 45 years of age, I have read it from beginning to end and it is a truly spectacular piece of writing! I read for two hours before bed last night, unable to put the book down until I finished the last chapter, crying quietly. This book moved me as few others have and I am a voracious reader.

I have so many questions, thoughts and feelings concerning the book but it’s going to take me a while to formulate them and a while to digest the book fully. It’s a book I can see myself reading again and again and getting something different, something more, out of it each time I take it up.

I just read about the synchronicities Mr. Thomas observed during the writing of The White Hotel and during my reading of his masterpiece, I couldn’t help but see the book as an exploration of the interconnectedness of everything. I love how he writes about the scent of pine (and quite synchronistically, when I opened the book to look for a passage about the pine trees, the book opened to the exact page for which I was looking!) and how Lisa finds comfort when she is able to see herself as having a continued existence. There is no past, present or future but a continuum on which we, as human beings, exist. Even death and the afterlife are blips on this continuum.

In certain parts of the book, I had an almost palpable sense of horror, fear, terror, and nausea. My pulse beat wildly but I still continued to savor every word, knowing that I would go into my 10 year-old son’s room where he was already asleep and check on him and give him an extra goodnight kiss before turning off the light to go to sleep. I couldn’t help but think of Kurtz in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and his final exclamation: The horror! The horror!

Thank you, Mr. Thomas, for writing such a life-changing, eye-opening novel— a novel that perhaps existed before it was written and published and a novel that will continue to exist ever after. I am also reminded of a couple of lines from Wordsworth:

In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

Vit Babenco

The White Hotel begins with an exquisite Freudian poem. The novel is dark as the history itself and full of alarmingly disturbing thoughts.

“At my first hearing of a dream, I became alarmed, for it told me that the dreamer is quite capable of ending her troubles by taking her life. Train journeys are themselves dreams of death.”

Destiny of an individual is decided long before one's birth and it is interconnected with the destiny of the entire world and our wishes hide in our dreams.

Leah

Theodor Adorno, in an oft-misappropriated quote, wrote that to compose poetry after Auschwitz is barbarism. Adorno did not, as it may initially seem, intend the Holocaust to signify the end of cultural creativity. Rather, it’s a remark that – against the broader critical landscape – inquires about reconciling a culture that produced Kant and Beethoven with the largest, most extensive, systematized killing in humanity’s history. There is a “tension between ethics and aesthetics inherent in an act of artistic production that reproduces the cultural values of the society that generated the Holocaust”; a tension that must be navigated by any writer or artist broaching the subject (“The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” A. Richardson, eSharp Issue 5 – Borders and Boundaries. D.M. Thomas, as author of The White Hotel (and instigator of the voluminous ensuing literary discussion) sensitively and adroitly writes a ‘Holocaust novel’ without falling prey to the compulsion to make the novel a parable or story of redemption.

(And it is this, the avoidance of ‘the redemptive power of suffering’ or ‘suffering as purpose’ that makes The White Hotel an essentially Jewish novel: it avoids the Christian teleology present in so much Holocaust literature).

To suppose the Holocaust should only be approached as abstraction is not a new idea. Direct literary narrative can’t examine the ‘silence of God,’ the vicious anti-human violence; non-fiction accounts, too often, reduce the subject to little more than tally marks and quotes about ‘The Jewish Problem.’ The literary world is rife with Holocaust narratives: they have been turned into commodities, the shock and horror (and sturm und drang!) has long given way to cautionary tales about hatred and brutality. The White Hotel subverts the common conception of Holocaust literature: it is, in parts, erotic poetry, epistolary exchange, narrative, historical document, and hallucination.

The psychotherapy sessions between Freud and the protagonist, Lisa Erdman, are used as infrastructure for Lisa’s third-person narrative. Freud is an enabling device and mouthpiece – certainly anyone, with even a modicum of experience with Freudian thought and analysis, would recognize Lisa’s symptoms (pains in her breast and pelvis, sexual hysteria and hallucination, and the transformative role of her mother’s sexuality) as Freudian in nature. Lisa authors a stream-of-consciousness poem, and further clarifies it (at the urging of Dr. Freud) into a fantastical, sexual, violent vignette.

From the 21st century, we know the inevitability of Eastern European Jewry in the 1930s and 40s; the herding of Jews to destruction in Poland, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia. The infernal drumming of the Holocaust is in the distance, with oblique reference to political and social unrest at different periods throughout the novel.

The novel abruptly drops us from Lisa’s dreamlike, comfortable (though frequently anguished) quotidian life to life during the war – bereft of the luxury she had prior – living in Kiev, Ukraine, poor and raising her son, Kolya. They are summoned – with the rest of the city’s Jewish population – to the riverside ravine, told they will be boarding trains (to camps, to Palestine, the furor of rumors overtake and transfix the evacuated Jews.

Of course, Sigmund Freud’s theories cast a long shadow over the twentieth century: the emergence of psychoanalysis, in conjunction with his extensive writing on behavior and nature, make him a prime lens and focusing agent on the events of the Holocaust and World Wars. He also, at times, cheapens the novel (though Thomas is good at keeping Freud as a device, rather than as a character); surely, the narratives and experiences would work as well without him, and Lisa’s ‘hysteria’ and psychosexual pain would be just as meaningful without the Freudian framing. (Indeed, her symptoms manifest obliquely – and directly – enough to draw the careful reader into the presumption of some kind of Freudian situation). The Freudian life and death instinct are two oppositional, harmonic forces that bookend the novel and the experiences of Lisa, the protagonist.

With Lisa’s ongoing breast and pelvic pain, her hallucinations and emotional preoccupations, her unreliable narration is assumed. How much can we trust her recollections? At what juncture, if any, do her preoccupations become surrogates for ‘real’ (as in, historically documented, agreed-upon) events? Leslie Epstein’s review, “A Novel of Neurosis and History” (New York Times, March 15, 1981), notes that Lisa is bereft of intellectual vigor and depth: she exists in a time, and circumstance, that would seem to court cultural exploration. And yet, in her narratives (both epistolary and third-person), she remains without intellectual identity and interaction.

At Babi Yar, Lisa – wearing her crucifix – is shot at, yet still alive in the mass burial pit. A German soldier spies her jewelry and pulls it off her neck, realizing she is still breathing: he smashes her breast and pelvis beneath his boots. Two soldiers, later discovering a flicker of life, subsequently rape her with a bayonet: a grisly, spare, and barbaric scene that finally frees her from life. And then, her experiences – her pains, her hysteria – acutely, rapidly focus: Lisa’s “Cassandra-like” premonitions and foresight, referenced throughout the novel, also predict her fate. Her ‘hysteria,’ then, isn’t manifested from past experiences – but the result of her future encounter with brutal soldiers, committing brutal violence, in a catastrophically brutal time. (Surely, too, with Freud and Lisa’s acknowledgement of foresight, this would explain the number of women experiencing hysteria some years prior to the Holocaust).

Extensive literary scholarship and criticism exists on The White Hotel, and with good reason: it is an unusual, phenomenal, profoundly moving piece of fiction, alone in its form and presentation. One of the most common criticisms leveraged against the novel addresses Lisa’s competing identities, her femininity and her Jewishness. There are protracted commentaries about which identity – the feminine or Jewish – subsumes the other. We are forced to confront, then, the nature of Jewish identity: Lisa is hardly living a remote, rural life on the shtetl in the Pale, she is a secular, cosmopolitan woman – the product of an interfaith marriage and a trained opera performer. Her Jewish identity hinges on her encounters with anti-Semitism; her Judaism is an abstraction, not a theological or cultural touchstone, and one she is forced to confront at Babi Yar.

Like many Jews, she exhibits a complicated (and even denialist) relationship to Judaism: she wears a crucifix, and – upon showing her gentile surname and paperwork to a German soldier -- is given the opportunity to escape the murdering. She remains, though, as Kolya (her son) cannot leave – and she is, ultimately, subsumed into the inevitable, inescapable fate of European Jews. She has internalized anti-Semitism, from her father, from a group of harassing sailors in her youth, from her estranged husband.

Discourse on The White Hotel means accepting a non-binary version of identity, motivation, and experience; that differences in ‘truth’ and ‘reality’ exist, and the distinctions between the two aren’t particularly important – especially not within the abstract narrative. A compulsion to reconcile the ambiguities and fluidity of the novel – with all varieties of reality into one, holistic experience, denies the novel’s very nature. The expectation of realism to succeed abstraction is short-sighted and contradicts the essential nature of conceptual fiction.

Steve

At the time of his conception of this novel, D.M. Thomas's thought process must have been along these lines:

I have yet to encounter any novel from any era that has done justice to the complexity of the human personality. I shall make my own attempt to portray a human personality true to its profound complexity, which to this point has been beyond the imaginings of other novelists.

The result is our immersion in the personality of Frau Lisa Erdman, an opera singer and at the outset a patient of Sigmund Freud. She has sought his assistance because she suffers from excruciating pain in one breast and in her genitals.

Should you need a simple plot summary, you can find that there. I too am going to speak of some of the events in the book here. If you have not read the book and are troubled by that, please go read the book now and return later.

One would expect some renditions of the sexual life and sexual fantasies of the patient in an account of her psychoanalysis. The initial sections of this book will be beyond your wildest expectations in that regard. The sex is hot, and by that I mean quite frankly that the sexual accounts in this novel are capable of arousing the reader himself. Call it pornographic if you wish. I care not. These sexual exploits are carried on with a single-mindedness by the participants that sustains it even as nearly every other guest in the hotel dies, or so it seems.

However, the description of the sex is riddled with imagery of incredible beauty:

He was convinced that stars were falling through the black sky outside their window and she argued that they were white roses. But then something that was unquestionably a grove of oranges floated down and they gave up whispering, in the wonder of watching it. The brilliant oranges glowed in the dark rustling foliage. The lovers went on to the balcony to see the orange grove fall in the lake. Each separate fruit hissed and was extinguished as it touched the calm water.

We then move to Lisa's life after psychoanalysis which is inevitably, unknown to us at the time, an extended train ride to the atrocity, the massacre at Babi Yar by the Nazis. Early in that phase of the novel when Lisa is touring scenes from her childhood with her step-son Kolya, she is overcome with an epiphany:

...she knew that she and the child of forty years ago were the same person. That knowledge flooded her with happiness. But immediately came another insight, bringing almost unbearable joy. For as she looked back through the clear space to her childhood, there was no blank wall, only an endless, extent, like an avenue, in which she was still herself, Lisa. She was still there, even at the beginning of all things. And then she looked in the opposite direction towards the unknown future, death, the endless extent beyond death, she was still there. It all came from the scent of a pine tree.

It is only much later that we learn the significance of that “scent of a pine tree.” Mr. Thomas's use of that image, an olfactory image if you will, is as skillful a use of an image by an author as any I have encountered in a long time. In fact Mr. Thomas's use of various styles, his ability to bend time to his purposes, and his utter poetry make this book a tour de force.

You will not read a more harrowing account of an atrocity, a mass murder than the one Mr. Thomas has created. It is emotionally exhausting. But during the course of it, we discover that each and every human victim of this savagery, even the babes, had a life--mental, spiritual, psychological--of a complexity as profound as Lisa's. When her Ukranian murderer mutilates her breast and her genitals, the areas of her pain at the outset of the novel, the affect on the reader is an experience not often encountered with fiction.

Luckily, Mr. Thomas helps us out of this emotional morass with an account of the afterlife at the end of the novel, or perhaps it is an account of some last fantasy of Lisa as she dies. You may chose depending upon your predilections in that regard. It is not a perfect afterlife, but it is amazing how soon the reader can be transported from the emotional devastation of the massacre to a feeling of hope.

You will never experience the scent of a pine tree in quite the same way for the rest of your life.

Speranza

RECIPE FOR THE SUCCESSFUL NOVEL:

Ingredients:

Take 30% sex

Take 20% Holocaust

Take 20% Freud

Take 10% death

Take 10% violence

Take 10% epistolarity

Spices: Add erotic poetry to spice up the meal and classical music to boost the price.

Be careful not to stir the ingredients together, each flavor should stand out on its own.

! Please be sure not to include any good writing, plot or an underlying message, as they will make the meal heavy and indigestible.

Happy reating!

David

Be careful picking this one up is not for the feint of heart, but if you need a "sense of proportion" in your life and a paradigm shift in thinking would do you good, give it a go. Read other peoples nicely crafted reviews if you want but I think its best to pick it up without a clue what its about.

Jonfaith

Harold at Twice-Told raved about this novel, but it was Emir Kusturica's interest in bringing it to the screen which inspired my reading. I felt the novel contrived and flat, though the premise is engaging: the very prescience of Freudian hysteria.

The bits that Thomas stole are the best in the book: shame on you, Donald.