Must be read

- The Storyteller's Secret

- The Other Boleyn Girl (The Plantagenet and Tudor Novels #9)

- A History of God: The 4

- Keto Diet for Beginners: 30-Day Keto Meal Plan for Rapid Weight Loss.

- Twisted Pride (The Camorra Chronicles #3)

- The Love Dare

- When No One Is Watching

- We Were the Mulvaneys

- Themes and Variations

- The Famous Magician

User Reviews

Ilse

From the very beginning, and throughout the whole of our affair, I had the privilege of knowing what we all find out in the end: the man we love is a complete stranger.

©hrissie ❁ [Back-ish -- Recovery Mode]

'He had said, “You won’t write a book about me.” But I haven’t written a book about him, neither have I written a book about myself. All I have done is translate into words—words he will probably never read; they are not intended for him—the way in which his existence has affected my life. An offering of a sort, bequeathed to others.'

In Annie Ernaux's auto-analytical text, Simple Passion, living within the parameters of a 'growing obsession' -- the 'exaggerated importance' of a passionate affair -- means surrendering to the void and ultimate meaninglessness of existence; being 'entirely at the mercy of that crucial moment' of encounter; slipping chaotically into-and-out of a contorted consciousness. It also means -- at one and the same time -- opening oneself up to the world: to the turpid aspects of our humanness. Alongside the vertiginous force of self-undoing, Ernaux testifies that through her lived out passion for A she 'discovered what people are capable of'. Moreover: 'Without knowing it, he brought me closer to the world.' But she harbours no illusions, for 'From the very beginning, and throughout the whole of our affair, I had the privilege of knowing what we all find out in the end: the man we love is a complete stranger.' True to the mental-and-material experience of desire, opposites see themselves in one another. Because, also, 'thanks to him, I was able to approach the frontier separating me from others, to the extent of actually believing that I could sometimes cross over it.'

Ernaux's is a starkly written, honest rendition of 'the signs of passion'. At no point does it attempt to obscure the fundamental reason of its existence: describing that sense of being 'wrapped up in a man'. It is about the defining Wait inscribed in all-consuming passion, where impenetrable absence engulfs all instances of non-presence and transforms experience into a series of absurdities known to those who have shared this condition. A condition of 'idleness' that is singularly 'lethargic', its captive 'slip[ping] into a semi-slumber' and responding to a disjointed and dramatically recalibrated conception of time, the 'interval of time' stretching between moments of encounter turning into 'an unbearable, interminable wait'.

'Now I was only time flowing through myself.'

'I experienced pleasure like a future pain.'

'Throughout this period, all my thoughts and all my actions involved the repetition of history. I wanted to turn the present back into the past, opening on to happiness.'

'In my dreams too was the desire to reverse time.'

'[...] the time which separates the moment when [these words] are written—when only I can see them—from the moment when they will be read by other people, a moment which I feel will never come. [...] This delay makes it possible for me to write today'

'Living in passion or writing: in each case one’s perception of time is fundamentally different.'

In the resultant eradication of a self's centre, passion becomes the kindred receptacle of trauma. An 'ordeal', as Ernaux puts it: 'I reflected that there was very little difference between this reconstruction and a hallucination, between memory and madness.'

The writing is acutely introspective and deconstructive, its intensity accentuated by the very disconcerting power and unfathomable quality of an unyielding passion. It is aware of itself as writing, and liberally fluctuates between observations on passion and the writing process, essentially thinking of them in intersecting terms.

'It occurred to me that writing should also aim for that—the impression conveyed by sexual intercourse, a feeling of anxiety and stupefaction, a suspension of moral judgement.'

'Quite often I felt I was living out this passion in the same way I would have written a book: the same determination to get every single scene right, the same minute attention to detail. I could even accept the thought of dying providing I had lived this passion through to the very end—without actually def ining “to the very end”—in the same way I could die in a few months’ time after finishing this book.'

'I felt I was living out my passion in the manner of a novel but now I’m not sure in which style I am writing about it: in the style of a testimony, possibly even the sort of confidence one finds in women’s magazines, a manifesto or a statement, or maybe a critical commentary.'

'Sometimes I wonder if the purpose of my writing is to find out whether other people have done or felt the same things or, if not, for them to consider experiencing such things as normal.'

'Of the living text, this book is only the remainder, a minortrace. One day it will mean nothing to me, just like its living counterpart.'

'To go on writing is also a means of delaying the trauma of giving this to others to read.'

...The understated beauty of this frank compendium is absolutely astonishing...

🌹🌹🌹

4.5 stars.

Eric Anderson

Every year there is excited debate about what author will be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature and this year one of the top contenders that readers were speculating about was Annie Ernaux. Since I had a fairly free morning and while I was waiting for the prize announcement to be made, I thought I'd get to reading the most recent book to be translated by this author whose work I fell in love with starting with “The Years”. It's very short – just under 50 pages! And it centres around the subject of a married man that the author/narrator had an affair with for a couple of years. It's an all-consuming passion which takes over her life for this period of time. Her focus is not on the details or moral drama of the affair, but the impact passion has upon an individual: “I do not wish to explain my passion – that would imply that it was a mistake or some disorder I need to justify – but simply to describe it.” In doing so, she illuminates how we can become completely entangled in heated passion in a way that defies all logic and reason. Ernaux uses her characteristically rigorous sense of self enquiry to raise larger questions about the nature of desire, imagination, time and memory.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Ernaux's writing is the openness of her narrative to take shape in the way which will best convey the meaning and heart of her subject matter. She describes how: “I felt I was living out my passion in the manner of a novel, but now I am not sure in which style I am writing about it, whether in the style of a testimony, or possibly even the sort of confidence that can be found in women's magazines, maybe a manifesto or a statement, or perhaps a critical commentary.” This book defies genre or any conventional form. Yet, its construction feels perfectly suited to what she wants to say and there's a masterful precision to her ideas. If most writers were to do this and discuss the book's construction so openly within the text it would feel intrusively self conscious, but with Ernaux it feels like a sincere and conscientious way to explore the subject matter. The book even moves from the past to the present tense because she realises that she's gradually being released from the grip that passion has on her which traps her in memories of her lover. At the beginning she's outside of the flow of everyday life, but by the end she's rejoined the stream of time and can reside again in the present.

Read my full review of Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux on LonesomeReader

I also made a video discussing this book which you can watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqO_tTy5AK4

Jana

This book reminded me of exactly how I felt when I fell for a married man. Intense and overwhelming chemistry was swallowing us. For me it was an experiment (I was very young and naive) and for him being fifteen years older it was a thrill of his own. I had never experienced such mind losing magnetism with any other man before and there was something so decadent in our relationship. I didn’t feel ashamed, I didn’t have a reason, he didn’t have any whatsoever guilt trips and I was 20 and living my student life with a full blown adrenaline rush.

But he was with a reason driving me mad and I was willingly doing this to him as well. Just, this kind of passion is so extreme that it makes you do things that you wouldn’t normally do; it makes you cross your moral boundaries without any guilty conscious nibbling. When I look back at those days, I roll my eyes although there was something so animal and wildly exciting when we saw each other for the first time so that unharming violent passion that we had was in a way appropriate for that time.

Nowadays I would never go into those kind of complicated relationships because of the numerous vivid overheated reasons and because of the countless hidden struggles and scars that are left behind. Just like Ernaux said and just like she thanks passage of time for knowing that.

But again, never say never. Old flames are not always dead matches.

Dave Schaafsma

“Sometimes I wonder if the purpose of my writing is to find out whether other people have done or felt the same things or, if not, for them to consider experiencing such things as normal. Maybe I would also like them to live out these very emotions in turn, forgetting that they had once read about them somewhere.”

Simple Passion is a short novella-length memoir wherein Annie Ernaux recalls a time when she is consumed by passion, describing a two year affair she had as a young woman--when she was at university--with an older, married man from Poland who was working in France temporarily. She couldn't contact the man, but waited every day by the phone for him to call and say he was coming over. We learn nothing of the man; we only learn the all-consuming obsession she has at the time where nothing else really matters, even though she knows that the desires involve undeniable indignities, and come to nothing over time. We don't get a sense of all the fun she has; quite the contrary, she becomes reduced to a kind of paralysis. She never expresses regret explicitly, but one can see the psychology of being reduced to "the other woman."

Even though Ernaux makes explicit attempts not to get too emotional or self-critical--to just focus on where memory takes her--I get the sense that she does have some regrets about how diminished she feels at this time, not knowing what to do about it, not being able to end it. I think plenty of people can relate to it.

Lisa

Nice summer read in the heat!

But_i_thought_

A rare combination of honesty and vulnerability.

Suzanne

"Whether or not he was 'worth it' is of no consequence. And the fact that all this is gradually slipping away from me, as if it concerned another woman, does not change this one truth: thanks to him, I was able to approach the frontier separating me from others, to the extent of actually believing that I could sometimes cross over it. I measured time differently, with all my body. I discovered what people are capable of, in other words, anything: sublime or deadly desires, lack of dignity, attitudes and beliefs I had found absurd in others until I myself turned to them. Without knowing it, he brought me closer to the world."

The above passage comes at the end of Ernaux's Simple Passion, and each time I read this small book, I do the same thing. I get to this part at the end where her lover returns, for a day, a moment. He is 38 now, upon return, youthful but weary (a perfect description of 38). I expect it will be like the end of The Lover--I read expecting this, each time, marveling at how Ernaux in her French elegance invokes Duras.

But then it fails. Or subverts expectation. The lover disappoints. He does not say what Duras' narrator's lover says, that he's always loved her. He is callous. And it is perfect this way, how it invokes The Lover and then rejects The Lover, as Ernaux notes that it was another woman entirely: "as if it concerned another woman" because of course it did.

I’ve long been drawn to Ernaux's writing, to her freedom--the freedom or courage she has to write her experience. Simple Passion is among my favorites, a book that chronicles an affair, that becomes about the erotics of writing, the pleasure of that, which is linked to the pleasure of the body. The shame, too, which comes later.

sofía

This summer for the first time, I watched an X-rated film on Canal Plus. My television set doesn't have a decoder; the images on the screen were blurred, the words replaced by strange sound effects, hissing and babbling, a different sort of language, soft and continuous. One could make out the figure of a woman in a corset and stockings, and a man. The story was incomprehensible; it was impossible to predict any of their actions or movements. The man walked up to the woman. There was a close-up of the woman's genitals, clearly visible among the shimmering of the screen, then of the man's penis, fully erect, sliding into the woman's vagina.

+ thomas ruff's nudes

-

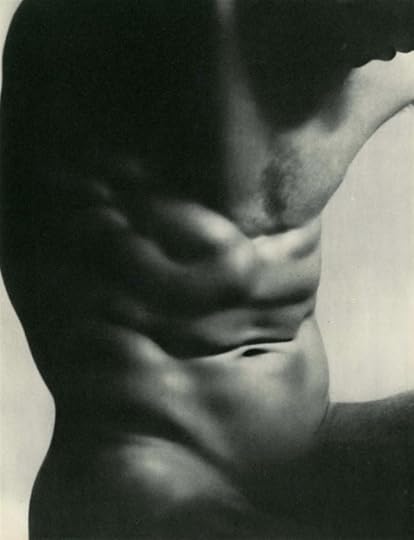

In museums I saw only the works representing love. I was drawn to statues of naked men. In them I recognised the shape of A's shoulders, his loins, his penis, and especially the slight hollow following the inner curve of his thigh up to the groin. I was unable to tear myself away from Michelangelo's David, filled with wonder that a man, and not a woman, had portrayed the beauty of a male body so sublimely. Even if this could be explained by the oppressed condition of women, it seemed to me that something had been irretrievably lost.

+ laure albine guillot

I wanted to remember his body with all my being—from his hair down to the tips of his toes. I could conjure up, vividly, his green eyes, the lock of his hair falling over his forehead, the curve of his shoulders. I could feel his teeth, the inside of his mouth, the shape of this thighs, the texture of his skin. I reflected that there was very little difference between this reconstruction and an hallucination, between memory and madness.

-

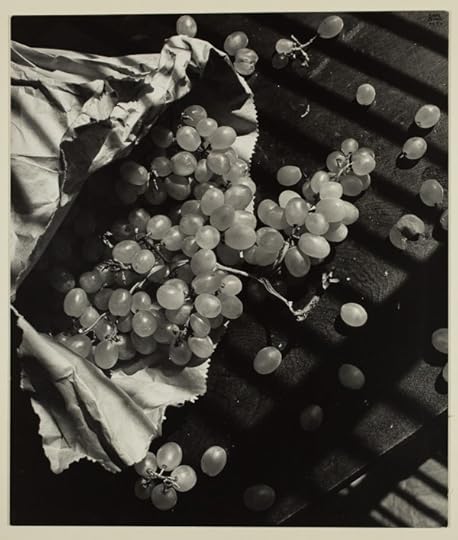

As soon as he left, I would be overcome by a wave of fatigue. I wouldn't tidy up straight away: I would sit staring at the glasses, the plates and the leftovers, the overflowing ashtray, the clothes, the lingerie strewn all over the bedroom and the hallway, the sheets spilling over on to the carpet. I would have liked to keep that mess the way it was—a mess in which every object evoked a caress or a particular moment, forming a still-life whose intensity and pain could never, for me, be captured by any painting in a museum. Naturally I would never wash until the next day, to keep his sperm inside me.

I would count the number of times we had made love. I felt that each time something new had been added to our relationship but that somehow this very accumulation of touching and pleasure would eventually draw us apart. We were burning a capital of desire. What we gained in physical intensity we lost in time.

+ ilse bing

-

Between last May, when I stopped writing, and today, 6 February 1991, the expected conflict between Iraq and the Western coalition has finally broken out. A 'clean war' according to the propagandists, although Iraq has already received 'more bombs than the whole of Germany during the Second World War' (this evening's edition of Le Monde) and eyewitnesses claim to have seen children stumbling through the streets of Baghdad like drunkards, deafened by the explosions.

Evan

"I do not wish to explain my passion -- that would imply that it were a mistake or some disorder I need to justify -- I just want to describe it." (p. 23)

I hate reading books like this, because they make me want to be in love again.

At the same time, the yin and the yang ... I love reading books like this. They are like bon bons. And they remind me of when my whole being was electrified and puffed up and full, and then of the aftermath when my insides exploded and left a wreck that jangled around like shattered metal and I couldn't move or think without feeling all of that. The insides kept ripping from the shards. The sinew heals with a lot of scar tissue.

This is one of those French reflective inner-thought books of super-concentrated yearning. It is like the diary of a woman who finds herself in a particular kind of limbo that happens when the afterglow of a love has passed, the passion has morphed, the desire to re-live it remains in memory, but the realistic distance of self-reflection has interceded. It's part Duras (not as oblique), part Catherine Millet (not as pretentious), and maybe someone else I can't place. It evokes those mixed confusing feelings that arise from coping, remembering and cherishing. The way Ernaux describes these feelings is very familiar. I recognize a lot in it. I've had many of the precise thoughts she describes, thoughts I've never seen described elsewhere.

It's a book about lovers who remain strangers, like all lovers, but who suspend disbelief and do not care. It's about the futility of recapturing a fantasy, but holding a memory as reality.

Books like this help us re-center, help us to remember that passion hasn't died; that the civil pleasures are all well and good and necessary for sanity. Yet, when we are at our height, we are irresponsible and oblivious to all but the oblivion of love that obliterates all.

This book could be accused of being slight, but it's well done; especially if you just want to sigh and dream and feel.

(KevinR@Ky 2016)

JimZ

A woman has an affair with a married man and describes her feelings about it. Sometimes her whole life during that two-year time period revolves around him...every waking moment of her day is devoted to thinking about him....is he thinking about me, what is he doing, when is he going to call... or after he drives off after they are briefly together she is sad he is gone. She really does not make any apologies for her affair to the reader, and that is OK by me. The memoir is from her heart and her brain. She’s a good writer. I read a number of her memoirs 20 years ago and hope to go through them again. I read ‘Positions’ (A Man’s Story) last year (4 stars).

Note

Apparently this novel is more commonly issued as ‘Simple Passion”. My version is named ‘Passion Perfect’. Same book.

Reviews:

• https://medium.com/a-thousand-lives/a...

• https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/bo...

• https://lonesomereader.com/blog/2021/...

Vishy

‘Simple Passion’ by Annie Ernaux was one of the books mentioned in Lance Donaldson-Evans’ ‘One Hundred Great French Books’. I haven’t heard of Annie Ernaux before and so decided to try this book. I read it in one sitting and finished it yesterday. Here is what I think.

‘Simple Passion’, at around sixty pages, is not really a novel. With wide spacing between lines and with luxurious space on the borders of the page, it could be called, at best, a novella or probably a long short story. It is not clear from the book whether it is fiction or a memoir. The classification on the back cover says ‘Literature / Memoir’. The narrator of the book describes the affair she once had with a married man from a different country who was working in Paris. The only way they communicated was by phone when the man called her and told her he was going to visit her. She then waited for him to visit, anxiously preparing herself – getting the right clothes, wearing the right makeup, getting food and drink for the evening, preparing herself emotionally – but also looking forward to the visit with a lot of excitement. But then he comes, they have intimate moments together, he leaves and then she is worn out. And she starts the long agonizing wait for the next phone call from him. At some point she stops seeing her friends, going out for movies or having any kind of social life as she is waiting for her lover’s phone call, when she is not working (this was during the days before the advent of the mobile phone). The narrator’s thoughts about this whole affair comprise the rest of the book.

‘Simple Passion’ is an interesting book. There is not much of a plot here – the plot can be told in two lines. The book is mostly about the narrator’s thoughts on life, love, longing, waiting, the agony of parting. I am pretty sure it will deeply resonate with anyone who has had an affair or even with anyone who has ever been in love. Annie Ernaux’s prose is spare and simple, but there are beautiful sentences in every page. Though I read it in one sitting, I read it very slowly and enjoyed lingering over those beautiful sentences. For example, she describes the brief time she spends with her lover as :

An interval of time squeezed in between two car noises – his Renault 25 braking, then driving off again

And she describes her feelings after her lover leaves like this :

As soon as he left, I would be overcome by a wave of fatigue. I wouldn’t tidy up straight away. I would sit staring at the glasses, the plates and their leftovers, the overflowing ashtray, the clothes, the lingerie strewn all over the bedroom and the hallway, the sheets spilling over on to the carpet. I would have liked to keep that mess the way it was – a mess in which every object evoked a caress or a particular moment, forming a still-life whose intensity and pain could never, for me, be captured by any painting in a museum.

In another place the narrator describes how she used to shop for new outfits to look beautiful for her lover when he visited her the next time :

In his absence, I was only happy when I was out buying new dresses, earrings, stockings, and trying them on at home in front of the mirror – the ideal, quite impossible, being that he should see me each time in a different outfit. He would only glimpse my new blouse or pumps for a couple of minutes before they were discarded in some corner until he left. Of course I realized how pointless new clothes were in the event of his feeling desire for another woman. But presenting myself in clothes he had already seen seemed a mistake, a slackening in the quest for perfection for which I strove in my relationship with him.

In another place the narrator talks about the imperfection of communication with her lover and how paradoxically, this imperfection is sometimes perfect.

At first I was discouraged by the obvious limitations of our exchanges. These were emphasized by the fact that, although he spoke fairly good French, I could not express myself in his language. Later I realized that this situation spared me the illusion that we shared a perfect relationship, or even formed a whole. Because his French strayed slightly from standard use and because I occasionally had doubts about the meaning he gave to words, I was able to appreciate the approximate quality of our conversations. From the very beginning, and throughout the whole of our affair, I had the privilege of knowing what we all find out in the end : the man we love is a complete stranger.

Sometimes we think that writing about something which affected us deeply helps us make sense of it and is therapeutic, but the narrator of the story says something different :

I know full well that I can expect nothing from writing, which, unlike real life, rules out the unexpected. To go on writing is also a means of delaying the trauma of giving this to others to read. I hadn’t considered this eventuality while I still felt the need to write. But now that I have satisfied this need, I stare at the written pages with astonishment and something resembling shame, feelings I certainly never felt when I was living out my passion and writing about it. The prospect of publication brings me closer to people’s judgment and the “normal” values of society. (Having to answer questions such as “Is it an autobiography?” and having to justify this or that may have stopped many books from seeing the light of day, except in the form of a novel, which succeeds in saving appearances.)

At this point, sitting in front of the pages covered in my indecipherable scrawlings, which only I can interpret, I can still believe this is something private, almost childish, of no consequence whatsoever – like the declarations of love and the obscene expressions I used to write on the back of my exercise books in class, or anything else one may write calmly, in all impunity, when there is no risk of it being read. Once I start typing out the text, once it appears before me in public characters, I shall be through with innocence.

Annie Ernaux ends the book with this beautiful passage :

When I was a child, luxury was fur coats, evening dresses, and villas by the sea. Later on, I thought it meant leading the life of an intellectual. Now I feel that it is also being able to live out a passion for a man or a woman.

I have to say that I have got the ‘leading the life of an intellectual’ part right – so I can say that my life is filled with luxury, in a way :)

‘Simple Passion’ is a beautiful, slim gem. It is a book to be savoured over a winter evening warming oneself next to a fire having a drink. Or alternately, it can be savoured on a warm summer evening, watching the sun set, while sitting outdoors in the garden and sipping a delicious cup of tea. I want to read other books of Annie Ernaux now.

Have you read ‘Simple Passion’ by Annie Ernaux? What do you think about it?

Ruben

This is one of the clearest, most honest and open accounts of an all-consuming infatuation I ever read. Boy, she got it bad. And therefore all the more respect for being so open about it.

My first book by Annie Ernaux was 'Les Années' which I loved because she placed her life in the broader context of the times. But it seems her other autobiographical pieces, such as Simple Passion and also 'The Happening', are more strictly personal. Here, in fact, she admits that during the infatuation she was completely uninterested in the world around her.

I also found the ending interesting as she reflects on how time will wash away the infatuation, how she will become a different person and how writing her experience down and publishing it will give it its own life.

4,5

Kelly

Honesty. That the first thing I love about this book. The extent of the honesty- to a pathetic, sad fault. But it is unashamed about it. And that's the other thing.

I was expecting the French to give it an increased sensuality or more of a dreamlike quality that would distract me from what was actually happening with the beauty of its expression. Instead, it gave it even more of a brtual edge, I think.

Fitting.

Grace Burns

I would drink in the sentences

that I thought betrayed his jealousy, the only proof of his love in my eyes.

I had the privilege of knowing what we all find out in the end: the man we love is a complete stranger.

(It is a mistake therefore to compare someone writing about their own life to an exhibitionist, since the latter has only one desire: to show themselves and to be seen at the same time.)

I reflected that there was very little dif-

ference between this reconstruction and a hallucination, between memory and madness.

Our Book Collections

- Last Night at the Telegraph Club

- The Best Things

- Heartstopper: Volume One (Heartstopper #1)

- I'm Thinking of Ending Things

- The Wrong End of the Table: A Mostly Comic Memoir of a Muslim Arab American Woman Just Trying to Fit in

- Hometown Girl Again (Hometown #5)

- You Are Not Alone

- Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope

- A Good Marriage

- Unplugged